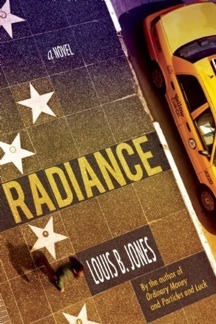

By Louis B. Jones

Hardcover, 240 pages

Publisher: Counterpoint, 2011

One of the criticisms aimed at the world of academia is the byproduct of its greatest virtue—that institutions should exist where great minds are given free reign. Critics complain of ivory towered extravagance where tenured crackpots churn out esoteric works of little or no apparent value: scientists with government grants devoted to the study of ant farms; the scholar whose unifying theory claims all of Literature is inherently phallic.

In his new novel, Radiance, New York Times Notable Author, Louis B. Jones, draws on the voice of physicist Mark Perdue from his 1993 work, Particles and Luck. In Radiance, the world of academia, though comical, is not a vacuum and professors are not innocent Siddharthas shocked by sights of sickness, old age, and death beyond the palace gates. Lest we forget, scholars and scientists live in the world.

Readers of Jones’ earlier comedy of manners will remember Mark Perdue as the newlywed Berkeley professor with a bright future in theoretical physics and a home in Marin County. Beneath the surface of this seemingly idyllic existence, Perdue grappled with infidelity, quantum mechanics, and the space-time continuum while he and his neighbor prepared for corporate seizure of their condominiums on Halloween night. But one needn’t read Particles and Luck to follow along here. Strictly speaking, Radiance is not a “sequel” so much as Jones touching on recurring themes through a familiar voice some 15 years down the road.

Radiance opens with a tone-setting meditation as the slightly older Mark Perdue experiences symptoms of a heart attack watching his daughter, Carlotta sing to a hall of concertgoers in Los Angeles:

Death—not some spooky or religious or abstract idea of it but just the practical everyday ingredient in nature—is everywhere close, everywhere a comfortable, cool medium to thrive in, right against the skin as it is…At the point of finally giving up oneself (one’s most cherished so-called self), it [Death] will come perfectly naturally for a man to—like water droplets appearing out of nothing—resolve again into the elements.

Perdue, we find, is considered “dead weight” by some of his colleagues, a former “whiz kid” having contributed nothing new to his field in over a decade. Now the worried father of an intelligent but brooding teenager, his chronic Lyme disease is taking its toll on his mental faculties. On top of all this, his wife recently underwent a 3rd trimester abortion after doctors determined the child would have lived a short and hopeless existence on life-support.

Perdue has taken his daughter to Los Angeles on a “celebrity fantasy vacation” a la American Idol, where she is getting three days of the rock star lifestyle treatment, in hopes it will assuage her grief at the loss of a brother-to-be. Perdue’s wife, Audrey, copes with the abortion by trading her career as a lawyer for carpentry, building houses for a non-profit organization.

The joy of watching his daughter’s confident performance is erased when she disappears with her new paraplegic boyfriend, Bodie. Meanwhile, sexual tension is ratcheting up between Perdue and his daughter’s attractive fantasy vacation escort, Blythe Cress. When he tries to find Carlotta and Bodie—they have disappeared into the LA night to visit the famed Hollywood sign—he gets arrested with them and, locked in a cell with Bodie. Once alone in closed quarters with the hypermoralist paraplegic, Perdue sees through Bodie’s needling idealism to the metaphorical recapitulation of his own life’s trajectory, and—just maybe—an unresolved problem in theoretical physics.

The Siddhartha metaphor is worth returning to for a moment, as this parable from Buddhism happens to share some common ground with Radiance. The prince, Siddhartha, who lived in cloistered abundance, saw four things the first time he went out into the world, the last of which affected him so profoundly that he forfeited the royal trappings of his life to ultimately become the Buddha. He saw a sick person, an old person, a corpse, and finally, a wandering holy man who had denied himself earthly pleasure—an ascetic.

The ideals and calling of an academician are, in theory, not so different from that of an ascetic—the commitment to a life spent seeking truth rather than material gain. But devoted as he might be to high-minded pursuits, Mark Perdue is not an enlightened being so much as a man of extraordinary intellect with worldly problems.

Louis B. Jones is a careful wordsmith and nothing is out of place here. It is almost as if pulling one word from these 219 pages would topple the entire framework. In referring to Blythe’s “djinn-like beauty,” or Bodie’s wheelchair as a “mobile stupa,” one sees an undercurrent of mysticism at the level of wordplay. Even Bodie’s name, a homophone of bodhi (as in bodhisattva), figures into Jones’ lapidary attentions. Radiance is layered throughout with such word choices.

It might be argued that the intersection of science and theology is uncertainty; the cutting edge of one field may require the language of the other to fortify itself. Some of Jones’ most lyrical passages are highly accessible interpretations of quantum mechanics couched in the language of metaphysics and religion. Perdue’s views may be shaped by the Scientific Method but he is incapable of such objectivity:

At every motion of “consciousness,” mortality intervenes, eternity intervenes, in every moment, too quick for the eye, in a billion consecutive brainflashes, like a deck-of-cards shuffle, so time and consciousness may seem to travel continuously and fluidly. As if there were no blackouts in between. As if there were no new personalities incarnated between. As if there were always a consistent “self,” or, “soul,” free-standing as a Doric column.

In some ways, Radiance questions Stephen J. Gould’s concept of “non-overlapping magisteria”—that scientists should stick to Science while philosophers and theologians should stick to matters of Truth and Religion. Jones, an artist, splits the difference by adopting the (wholly credible) voice of a physicist who goes right to the edge of metaphysics and ethics without getting mired in fuzzy poetics. With a roshi’s clarity, Perdue’s ruminations on physics and his own life become direct insights. But even these are difficult to live with as evidenced by the difficulty of real-life decisions and their moral impact—such as when the disabled Bodie presses Mark on the decision he and his wife made to go through with an abortion of a malformed fetus.

Radiance is filled with very human beings, misgivings and all, living in the fallout of our Western culture of convenience and shows us one man’s attempt to pull back the quotidian veil overlaying reality.

Jones is always timely, marrying today’s difficulties to archetypal themes—how flawed but ultimately good people struggle on the journey. Radiance shines like its name, richly rewarding, lambent, charitable. I look forward to hearing more, much more, from Louis B. Jones.

Smart, careful, lovely review of book that is same. I look forward to reading more, much more from reviewer Matthew M. For an interview with LBJ on Bibliocracy Radio (KPFK) download, free, from KPFK archives.