By Rebecca Solnit

Hardcover/Paperback 167 pages

Publisher: University of California Press, 2010

“An atlas is a collection of versions of a place, a compendium of perspectives, a snatching out of the infinite ether of potential versions a few that will be made concrete and visible.”

This passage is taken from the opening preface of Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. An introduction follows, explaining the author’s intimate relationship with this place as a resident for over thirty years, one where she is “constantly struck that no two people live in the same city.”

This multiplicity of perspectives on a place is illustrated by the book’s collaborative construction. Solnit gathered a team including eleven fellow writers, twelve artists, three cartographers, three researchers, a designer, and the San Francisco Estuary Institute—not to mention the photographers and the countless interviewees and experts quoted throughout—to produce twenty-two beautiful, ingenious maps and essays to celebrate the many histories, presents, and futures of the Bay Area.

These maps and essays encompass a wide swath of land and a long period of history. The writers and artists examine their subjects in intimate detail, as well as grand scope. Map 1, for instance, is titled “The Names Before the Names: The Indigenous Bay Area, 1769.” On it, one sees the former locales of dozens of native tribes, as well as the Spanish missionaries that had begun their infiltration. The accompanying essay, “A Map the Size of the Land” describes the methods by which Spaniards and Anglo-Americans were responsible for not only decimating native communities, but also distorting the histories of interrelated, yet unique, tribes.

Each map and corresponding essay opens a window on an unexpected intersection of place and culture in the Bay Area. One takes you on a voyage through the Bay’s beautiful green spaces to learn about the women who’ve protected them; another, into one of San Francisco’s old movie houses (of which few remain) to gain an understanding of the city’s pivotal role in early film-making.

Several maps shine lights on some of the area’s dark histories and shady constituents. One of my favorite chapters explores the “Right Wing Of The Dove: The Bay Area As Conservative/Military Brain Trust.” The map pinpoints the many power centers of the machine—military bases, corporate headquarters of multinational war profiteers, fuel refineries, and research centers including UC Berkeley—that represent a stark contrast to the stereotype of Northern California as a bastion of peace and love. Solnit pens the accompanying essay, “The Sinews Of War Are Boundless Money And The Brains of War Are In the Bay Area.” She writes, “This, to me, is the real essence of the Bay Area: it contains both Bechtel and Global Exchange…” Furthermore, “much of the rest of the world doesn’t even know.”

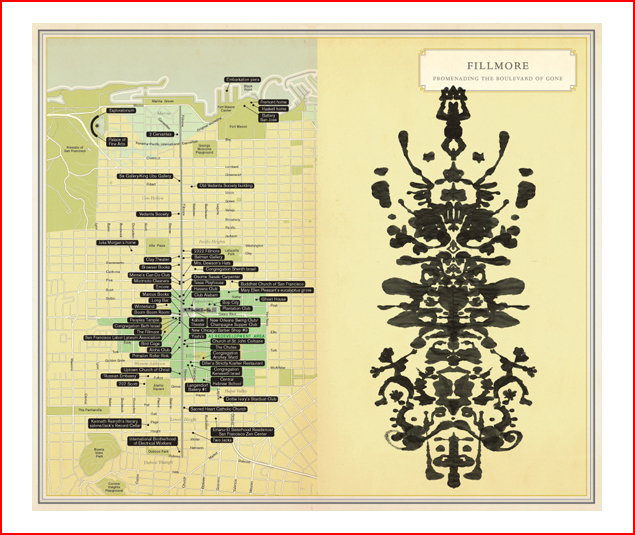

One can ride the 22 Fillmore bus along its route from the Marina to Bayview to understand the city’s economic disparity, as well as the historic Fillmore neighborhood’s massive changes throughout the decades. Stroll the streets east of Mission Street to hear the stories of undocumented workers, chart the boundaries of gang turfs, and all the while gain a sense of the pride and community that exists there.

Creativity abounds in the artwork, writing, and map-making, as well as in the minds of the contributors; several pairings inter-splice seemingly unrelated topics with wonderful cogent, results. One map locates monarch butterfly habitats alongside queer public spaces. Another uses red dots to indicate the ninety-nine murders in San Francisco during 2008 amongst the city’s Monterey Cyprus trees. Yet another maps the Zen Buddhist Centers of the Bay Area to highlight salmon migrations. The respective authors weave intricate narratives to explain the relationships, and challenge the reader to look at areas in a different way.

Solnit makes clear that “This atlas is a beginning, and not any kind of end.” In doing so, she leaves the reader with an encouragement to explore the Bay Area, as close or as far from your niche as you care to venture. On any given day, at any given point, you will be able to chart your own map, write your own tale—or, perhaps, engage with those around you to discover another path.