Australian-born photographer Kate Seabrook has called Berlin home since December 2011. She has documented train systems in Berlin, Prague, and Budapest. Creosote Journal caught up with Seabrook in Berlin to talk about the process of photographing train lines start to finish, her relationship with transit and typography, and her plans to publish Endbahnhof as a book.

We are a long way from Australia. Why Berlin?

I first visited Berlin in the winter of 2006. I was sleeping on the floor of an apartment on the corner of Warschauerstraße and Grünburgerstraße. The heating broke for two days and it was the coldest I have ever been. I was (and still am) fascinated by the fragmented and constantly evolving nature of the formerly divided city. It feels like an unfinished jigsaw puzzle and working out how all the pieces fit together is what has inspired a lot of my photographic projects.

How did you first get interested in photography?

Apart from a couple of short workshops, I have not formally studied photography. I first picked up an SLR about five years ago. At the time I was immersed in Melbourne’s underground music scene, so I just started shooting gigs and took lots of terrible photos. Eventually they got better and people started calling me a photographer. I also enjoyed walking around my neighborhood in Melbourne’s inner north taking photos of verandahs, signs, and cats.

Who are some of your photographic idols?

William Klein, Robert Frank, The Bechers, Martin Kollar, Warren Kirk, Annie Leibovitz, Nan Goldin.

What format do you generally use? Do you work in any other artistic mediums?

Most of my work is shot on a DSLR. My background is in live music photography and being able to switch quickly between ISOs is very important to me. This is also important when documenting subway systems where some stations are brightly lit and others very dark. I do have an Olympus Trip 35, a lovely old Voigtländer rangefinder and an olive green Werra which I will load up with some cheap film and take wandering when I feel like a break from digital perfectionism. The films will often sit there for at least a year before I get around to having them developed. I think it is healthy to encourage the delayed gratification of film.

What does transit mean to you?

I grew up in the southern suburbs of Sydney and have always been fascinated by the bustle of the big city. I get a kick out of being able to confidently navigate the metro system in a country on the other side of the world, especially one where I barely speak the language. It’s empowering. I have spent so much time navigating the Berlin U-Bahn that if I am running late for an appointment on one side of town, I know which carriage to board to get there fastest. If there is a delay on my line, I can often choose an alternative route at a moment’s notice. This is hard won and very useful knowledge.

How about fonts and typography? Living in Berlin, we are surrounded by a strong design culture. How does design influence your work?

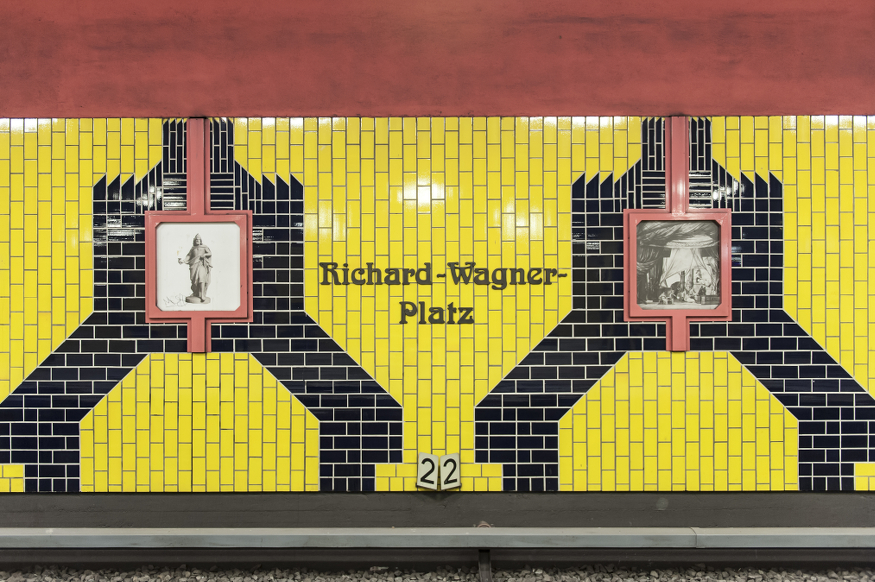

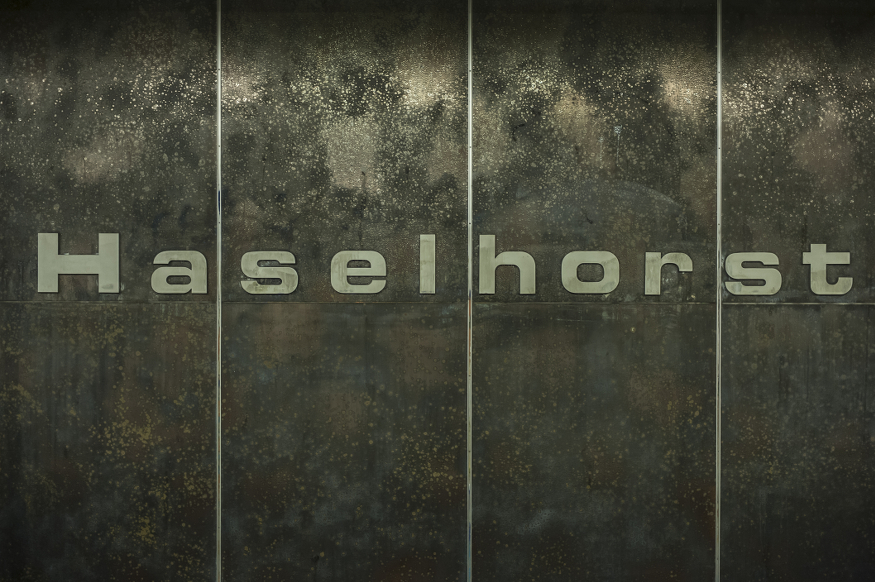

I have a personal obsession with 70’s design and the Berlin U-Bahn is particularly rich with examples from this era. My favorite stations are mostly along the U7 between Berlinerstraße and Rathaus Spandau. I love tracing the development of 70’s pop art morphing into 80’s postmodernism during the journey. These stations were designed by Rainer G Rümmler. Pankstraße station on the U8 (also a Rümmler creation) is another favorite for the use of the fabulous ’70s Octopuss font designed by Colin Brignall. Coincidentally, the same font was also used for the cover art of a Blondie release of The Tide Is High.

Changing lines at Fehrbelliner Platz is like going in a time machine. The U7 platform is a bold Rümmler design with a bright orange arrow guiding the train into the tunnel. Upstairs on the U3 platform you can see a more austere and classical early 20th century design by Wilhelm Leitgebel (hyperlink). More often than not, I will hone in on the typography and tiling rather than taking photos that show the wider atmosphere of the station and commuters.

How did you arrive at the concept of photographing the Berlin train system?

When I arrived in Berlin in late 2011 I already had an idea that I wanted to travel to the end of the U-Bahn lines and photograph what I found there. Shortly after this I caught the U7 all the way to Rathaus Spandau on the way to an unrelated photo expedition. Seeing the wild assortment of colorful stations through the window convinced me that perhaps the journey was what I should be documenting. I photographed the first line pretty soon after that, in January 2012.

What is your process when you photograph an entire train system?

Prague and Budapest were both shot in a single day. The Berlin project happened over a much longer period of time, as I was simultaneously dealing with all the challenges that come with setting up a new life on the other side of the world. All three systems were photographed from end to end in order of stations. I would travel to the end of the line, take the first photo, then get off at each station along the line and get the shot before the next train arrives. In Berlin this would normally be every 4 minutes, in Prague every 7-9 minutes. Budapest was the most challenging because at times the trains were coming every 2 minutes or less. This made it tough to get the shot I wanted, but it also meant that I managed to shoot the entire system before dinnertime! Due to time constraints and regulations, all photos were taken handheld without a tripod.

Any interesting stories or unusual connections made while photographing train stations in Berlin, Budapest or Prague?

There was an older gentleman in Budapest who was very concerned for my safety and herded me back from the edge of the platform while I was taking a photo. That was kind of sweet. I met a lovely scruffy dog named Stuplik and his human at a station on Prague’s green line. A fairly intoxicated man asked me to take his photo at Zoologischer Garten in Berlin and repeatedly jumped in front of my camera when I refused. The truth is, most people don’t notice me, especially in the more touristed areas.

Any upcoming exhibits, books, projects you are working on at the moment?

I am planning on turning Endbahnhof into a book, or possibly a series of books. At the moment, the majority of my focus is on shooting. I’m not sure when the project will be finished, but I definitely want to document a wider array of metro systems. I would also love to exhibit the series but need to find the right space and work out how I can best present such a large number of photographs.

Have you gained insight about transit based on your close study of the systems in Berlin, Budapest and Prague?

It is fascinating to note the similarities and differences between metro systems, specifically, how they work and how people use them. For example, the concept of ‘peak times’ varies from city to city and not knowing this was one of the reasons it took me so long to photograph the Prague metro. I found it interesting in Prague that instead of having signs along the platform telling you when the next train is due to arrive, there is a small counter recording the minutes since the last train departed. This information only makes sense if you know the frequency of the train schedule on any given line or time period. I had an anxious twenty minute wait in Prague near the end of my shoot, wondering if any more trains were going to show up so I could complete the project.

I’m also interested in how metro systems crudely chart the evolution of a city’s development. Their ever expanding lines can symbolize progress, hope, greed, political grandstanding, and so on. Often a single line can span many decades of history and architectural styles, creating a kind of visual Frankenstein history book. Many metro stations have been designed to please the eye or to make it easier to recognize your stop. Something as simple as a sign, a typographic feature or a picture in a metro station can be the clue that conceals a fascinating story of the city.

Outside of your work with transit systems, what other photography do you do?

My other projects include Housepeeking,which chronicles the living spaces of couples, and Strawberry Sundays, a documentation of the giant strawberry huts that pepper Berlin throughout the summer months. I am doing less live music photography these days and focusing more on taking photos of musicians behind the scenes.

Are there other train systems that you wish to photograph?

Definitely. I have plans to document more metro systems in Europe in the style of Endbahnhof. Not so much the obvious ones though. You will have to wait and see where I end up next!

You can find more from Kate Seabrook on her website. The entire Endbahnhof series can be found here. This is the first of a two part series of her work on Creosote Journal.

I am amazed that photographer Seabrook was able to present her brilliant focus on the hardware of transit while conveying very little of the human presence of such systems. In her commentary she mentions a couple of encounters with people and I’m glad for that. Her graphic and architectural interest is an interesting setup for guiding her development of the subject. Great subject to clearly illustrate her sharp techical skills. Documenting the multiple peaks in ridership along the same line is a fascinating phenomenon that might interest her engagement. Enjoyed the interview very much. Thanks.