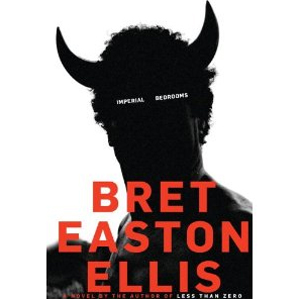

By Brett Easton Ellis

Hardcover, 192 pages

Publisher: Knopf, 2010

Bret Easton Ellis does something few writers manage to do: he upsets people. He offends them. He provokes a strong reaction. It’s not the fact that sex and violence turn up in his work; those can be found in the work of so many other writers. Rather, it’s the idea that his work is meaningful, that it qualifies as literature, and social commentary of a kind, that seems to piss people off or strongly divide opinion. Ellis portrays wealth, privilege, naked materialism, and the amoral exercise of power with a curious mix of lurid detail and condescension. Some wonder if he’s showing us shimmering visions of jet-set ennui and Hollywood hell in order to satirize it, or if that underworld—often exaggerated to the point of caricature—is more of a self-portrait of how Ellis feels and dreams. At least one reviewer has followed this interpretation to conclude that Ellis is sick with the very thing he pretends to ridicule.

In the opening pages of Ellis’s most recent novel, Imperial Bedrooms, the author seems to claim otherwise. The narrator of Bedrooms, it turns out, is the “real” Clay whom “the author” (Ellis) wrote about in first-person a quarter century ago in his breakthrough novel Less Than Zero. Clay says of the author, “He was simply someone who floated through our lives and didn’t seem to care how flatly he perceived everyone or that he’d shared our secret failures with the world, showcasing the youthful indifference, the gleaming nihilism, glamorizing the horror of it all.” There had been a movie made after the novel, about which Clay says “The reason the movie dropped everything that made the novel real was because there was no way the parents who ran the studio would ever expose their children in the same black light the book did… so the source material—surprisingly conservative despite its surface immorality—had to be reshaped.”

Julian Wells, we learn, didn’t die as the movie version of Less Than Zero had it. Not in a cherry-red convertible, O.D.ing on a highway in Joshua Tree. No, his body was dumped behind an abandoned apartment building in Los Feliz after he’d been tortured to death. What follows is, in a way, the story of how Julian really died, through the filter of Clay’s paranoid downward spiral. And Clay, now an adult screenwriter and producer, is the lowest kind of Hollywood scum; an amoral creep, exploiting everyone he can, even taking pleasure in the pain he causes others. He is also pathetic: alone and lonely, depressed and miserable, staring into the void of an empty life and without any meaningful connections to anyone else. Even as he exploits young actors and actresses, sometimes brutally, he desires genuine affection in return—which he knows he can never get.

Clay is prey as well as predator. From the book’s first pages, he is being stalked, hunted even, given cryptic and not-so-cryptic threats, which he treats with disregard—suggesting he has a wish for death. The dense plot only gradually yields to reveal the players who are behind the schemes and power moves. While I found nothing to admire in the characters themselves, I wanted to see where the book went—how it all shook out—and Ellis is gifted at creating a sense of suspense and stoking one’s curiosity.

In the opening self-critique, Ellis’s claim about Less Than Zero—“Surprisingly conservative despite its surface immorality”—resonated with me. It validated the intuition I had about Less Than Zero’s author after I read it. The book did glamorize the horror—teen junkies lying poolside (as their parents ski in Aspen), party-hopping and hotel-room-fucking, covering the tears in their eyes with perpetual sunglasses—but the ultimate destination it drove towards (and came from) was a place of deep disappointment, hurt, and outrage. It was a novel written by a very young man who had been totally disillusioned, was perhaps an ex-romantic, and wanted to write a book that—by showing the nightmare world of their absence—affirmed real human values.

There is less glamour in Imperial Bedrooms than there is in Less Than Zero. There’s a lot more horror, and it’s of a pretty grisly nature. The novel seems to come from such deep cynicism it almost negates any social commentary it could make—it’s so relentlessly dark that it becomes nearly monotonous. I say nearly, because it’s also undeniable that Ellis, as a writer, has deepened his craft over the many years since Less Than Zero, and that in Imperial Bedrooms, he’s created a work that is both terrifying and hard to stop reading. The short, compact chapters come at you like the threatening text messages that keep appearing on Clay’s iPhone—from someone who is out there, somewhere, watching him.

There are powerful themes being worked out in this novel—surveillance, stalking, exposure, power, possession, and fame are different heads of the same violent beast. There’s an inversion of the usual idea of Hollywood where being seen and known is equated with success. In Imperial Bedrooms, the power lies in being hidden; the victims are the ones who are seen, known, consumed, and ultimately destroyed. The grisly violence on the US border with Mexico, in Ellis’s blurred conception of Southern California, is inextricably linked with the air-conditioned retreats of Beverly Hills—the elite world of showbiz is collapsed completely into the world of terror, corruption, and mayhem.

While Imperial Bedrooms is, as far as I can tell, intended as satire, sometimes it seems like the shocks it delivers don’t have much of a point—slaps for the sake of titillation, rather than slaps to the face to wake the reader up to some ugly truth they’ve been ignoring. Great satire does more than shock and appall you, it also suggests a more human or genuine world—subtly, and never pedantically, but there is some glimmer there. This is true of West’s Day of the Locust, whose shadow stretches over this book though the two bear little resemblance. Despite the care with which Ellis has constructed his newest nightmare, Imperial Bedrooms winds up feeling like a dead end.