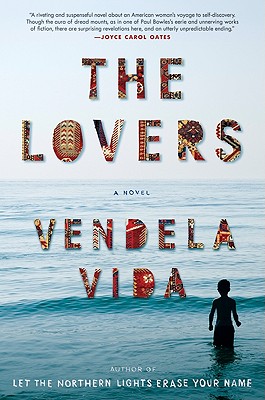

Vendela Vida

Hardcover, 228 pages

Publisher: HarperCollins / Ecco, 2010

It’s foolish to expect to escape yourself in another country. Writers tend to remind us of this, we might even say this is part of what separates the genre of travel writing from writing about travel (the first lies by selling us a dream, the second tells us an unpleasant truth but masks it in fable so we can bear it). What Yvonne, a middle-aged teacher from Vermont who has recently lost her husband to an untimely death, finds on a trip to Turkey is a confrontation of sorts; an encounter with unknown aspects of herself along with the immense unknown of the other country. What she brings to the experience shapes what she looks at, what she touches, and the outcome is thrown back at her through the prism of a society and culture she has little comprehension of. Though Yvonne and her husband visited the same stretch of coastal Turkey years before on their honeymoon, Yvonne finds it unrecognizable.

All this feels very true to life, and Vida’s straightforward prose renders it in sharp, wintry light. In spite of this clarity there is a dreamlike sense to the novel, a sort of drift from one incident to another, the scenes and encounters like small clues to a mystery that the reader begins to suspect won’t be revealed. There is the rented car she ruins by driving over fresh tar; the owls she finds hiding in the house she is renting; the presence of bondage gear and other erotica in the house; the appearance of the owner’s wife, who reveals to Yvonne this house is a getaway for her husband and his mistress; and, most of all, the young boy on the beach, gathering shells, and his incomprehension as it meets Yvonne’s desire for—what? To please him? To know him? Or, in some unconscious way, to possess him?

Though Vida’s style is not long-winded, there is nonetheless a slowness, a lingering over particulars, a sense of the long take and occasionally, of the figure grown small in a large frame. You are reminded of one of those windswept, austere Ingmar Bergman films, where tragedy looms close over a desolate and beautiful coastal landscape. There is a deliberate coolness in this style, an emotional distance that serves as counterpoint to the turbulent emotions the characters are feeling. Another cinematic reference came to mind: the meditative opening sequence of Atom Egoyan’s film The Edge of Heaven, set in a coastal village in rural Turkey.

The Lovers is about what happens after love. The title itself may be read as an ironic one. It conjures romantic love, of which there are only shadows and absences in this story—there is no rendering of passion in it. There is a remembered trace of what was there at the beginning of Yvonne’s marriage, but the story’s main action unfolds the excitement and nausea of life after its end. There is the bittersweet aftertaste of a long, prosperous, and too predictable relationship, mingled with the shock and surprise of her husband’s sudden death. The tragic and the ordinary are inextricably mixed.

Wanting to recover the unrecoverable: this is what we’re left with, the desire we’re left with, after someone dies. It’s also what we find in ourselves as we age, and look back at the time we can’t retrieve. Yvonne’s interior unrecoverables surround her with echoes, and her efforts to put things in their right place while traveling in Turkey are doomed to be inadequate: the manipulation of symbols and talismans, magic by imitation. Yvonne is haunted by her husband’s death, but she’s also lifted into weightlessness by her new freedom to define herself. This atmosphere of weightlessness—a sense that anything could happen—pervades The Lovers. It’s a combination of anxiety and wonder, and the sharp awareness that solitude brings.

Though lightly described, the book’s conclusion in Cappadocia evokes the landscape beautifully (“the landscape was lunar, everything white and gray”), setting the stage for a conclusion that feels startling, cut loose from reality, despite there being nothing magical about it. Vida maintains, here as in the rest of the book, that the sense of unreality in her fiction is not accomplished through bending the world through a weird prism or implying the workings of the supernatural, but rather by vividly conveying a sense of the limitation of our own knowledge when faced with the complexity and difficulty of the world as it is. It’s this sensibility, combined with the use of far-flung locales, that warrants the comparison to Paul Bowles that Vida has earned. Like he did, she reminds us that it is still possible to be lost in the world, and that this may be the same as being lost in ourselves. This condition is not distant, nor is it dependent on where you are; the traveler finds it because they carry it inside them. One day, they turn a corner and have no idea who they are. And they have to remember, and recover.