100 Years of the San Francisco Symphony, with Larry Rothe

Early next month, the San Francisco Symphony will host “Barbary Coast and Beyond: Music from the Gold Rush to the Panama-Pacific Exposition” bringing to life sounds from the City’s early history. In contrast, the Symphony just completed its American Mavericks festival, where it performed avant-garde works by living and recent composers, including Terry Riley, Harry Partch, Meredith Monk, and John Adams. It’s all part of the orchestra’s 100-year anniversary, which they’re celebrating for the 2011-2012 centennial season.

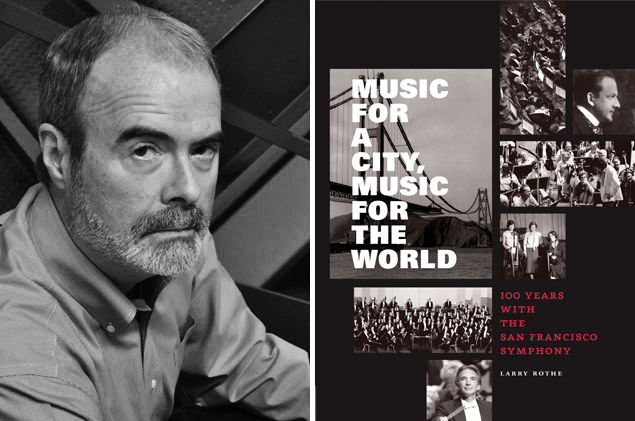

The occasion also saw the release of a new book, Music for a City Music for the World: 100 Years with the San Francisco Symphony, published by Chronicle Books. Written by long-time in-house editor Larry Rothe, previously co-author of For the Love of Music: Invitations to Listening

, the book charts the history of the orchestra as it rose to national prominence. I caught up with Larry for a talk about the book and about the history of the Symphony. [Full disclosure: I used to work at the San Francisco Symphony. Also, this interview has been edited and condensed.]

J: How does the history of the San Francisco Symphony reflect the history or character of its home city, and the things San Francisco is known for, like new technology, being a frontier city, an arts city, and so on?

LR: San Francisco was always known as a music loving town. The facts really bear that out. Even in the Gold Rush days, lots of musical acts and orchestras and singers came through here. An early history of the Symphony’s first decade claimed that the catalog of visiting musical acts covered seventeen single-spaced typed pages.

The San Francisco Symphony from the start was an orchestra that reflected its city. It was founded as part of San Francisco’s revival after the earthquake. The same spirit that rebuilt the physical infrastructure led to the birth of the orchestra and regeneration of cultural life.

J: A century is a long time to distill in a book. How did you approach this when writing Music for a City?

LR: I wanted something that wasn’t just a promotional piece, but a serious history. And that’s what everyone at the Symphony wanted. So I was able to look at the valleys as well as the peaks.

I wanted to look for the human story. I wanted to trace Symphony history according to music directors’ tenures, mainly because every music director put a stamp on the period over which he presided. Whether that was really extraordinary (as in the case of Pierre Monteux) or not so extraordinary (as in the case of Issay Dobrowen in the 1930s, or Enrique Jordá in the 50’s).

I was also drawn to some of the quirkier parts of our history. For example, in 1919 a player piano was on stage with the orchestra, acting as soloist in a piano concerto. That might strike us today as a kind of Barnum and Bailey act, but it was a serious presentation back then—not to mention something that took enormous skill, since orchestra and “soloist” had to remain in perfect synch.

J: When did the SFS start to get a name nationally?

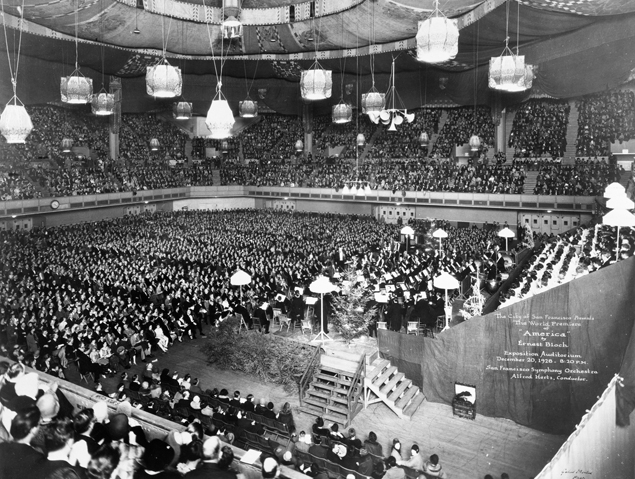

LR: It began to get a name, nationally, way back in the 1920’s, when Alfred Hertz was here, our second music director. Not many people today know about Alfred Hertz, but he’s really one of the unsung heroes of American music. A German conductor, he had worked with Gustav Mahler at the Metropolitan Opera. He was a master, and he started packing in the audiences. Under him, the orchestra blossomed.

In 1925, Hertz and the orchestra made the first San Francisco Symphony recordings. The Victor Talking Machine Company, which became RCA, was a national company that was already recording the Boston Symphony and the Philadelphia Orchestra. For an East Coast firm to commit to a West Coast enterprise in the mid-1920s was a major statement. California was still a long way off, on the far side of the country. There must have been something out here, for Victor to commit themselves that way. The recordings from that period really bear that out. You can also look at those first recordings as an early harnessing of technology. In 1927, Hertz appeared on the cover of TIME magazine. People knew about this orchestra on the West Coast.

But remember that, for a long time, our season was shorter than the seasons of other major North American orchestras, because we had to share the stage in the Opera House with the Opera and the Ballet. It was really when the orchestra moved to Davies Symphony Hall that an amazing period of growth started. Which is not to say that it wasn’t a fabulous orchestra back in the 1940’s, with Pierre Monteux—before Herbert Blomstedt and Michael Tilson Thomas came on, Monteux’s era was one of the high points in the orchestra’s history. In 1947 Monteux led the orchestra on one of the most extensive tours that any American orchestra has made: 56 concerts in 57 days, across the country.

J: So, you have a lot of perspective from looking back over the last 100 years of this orchestra. Now I’m going to ask you to prognosticate—what are the next 100 years gonna be like?

LR: (laughs) I have no idea! The core repertory will remain, but there will be a lot of innovation. There will be lots of changes that are absolutely impossible to predict. But one thing that music and any art gives us is an anchor. We listen to music written 100, 200 years ago because it continues to touch us, and there’s nothing that suggests Bach and Beethoven and Brahms won’t continue touching us for the next 100 years. That’s going to stay. It has to stay. It’s who and what we’re about.

J: At the same time, the SFS is known for doing a lot of contemporary music. There’s a special connection the San Francisco Symphony has with John Adams, and I know you’re quite familiar with him and enjoy his music. Can you talk a little bit about that relationship?

LR: John came on board as New Music Advisor in 1978, helping review scores that were coming in. When Edo de Waart came here as music director in 1977, he made it known that he wanted to play a lot of contemporary music, so he was inundated with scores and couldn’t handle them all himself. Edo and John struck up a great professional relationship almost immediately.

Four years after John came on board as New Music Advisor, he became our first composer-in-residence. While he served in that capacity, we commissioned him to write several pieces.

The first big one was Harmonium; that was a work for chorus and orchestra. That helped establish John as an up-and-coming composer. In 1985, he wrote Harmonielehre on commission from the Symphony. That has turned out to be a seminal work of late 20th Century music. It inspired a lot of young composers at the time. It announced that there was still a lot to be said in tonal music. Incidentally, the San Francisco Symphony recently released a new recording of the piece by Michael Tilson Thomas and the orchestra.

Our relationship with John Adams has continued. We gave the North American premieres of two works we co-commissioned: El Niño and A Flowering Tree. Absolute Jest, which he wrote for the centennial season, was part of a multi-year commissioning agreement that we entered into with John back in ’01. That agreement also resulted in My Father Knew Charles Ives, in 2003.

J: In your book, For the Love of Music, which you co-wrote with Michael Steinberg, you talk about the connections between writing and music, and the challenges of writing about music.

LR: The task is to try to examine the feelings music stirs—how, in a sense, the music leads to those feelings. If you can somehow verbalize this, you begin to understand emotions, thoughts, responses you may not have understood at first. Music can lead you into places you may not have known were there. In attempting to describe them, your world enlarges, your knowledge of yourself enlarges.

Signed copies of Music for a City, Music for the World are available here.