The tablet came before the book and after the book, historians might say one day, and describe the notion of a book, with groups of pages bound together, as representing just a developmental detour in the history of the tablet. This year, like most people who are both interested in books and technology, I followed coverage of the iPad’s debut pretty closely. And when I stopped by the Apple store on Stockton and Ellis in San Francisco to check one out, it struck me that there was something about the feeling of the device that was satisfying in an eerie way, that made sense and seemed to echo something out of the past.

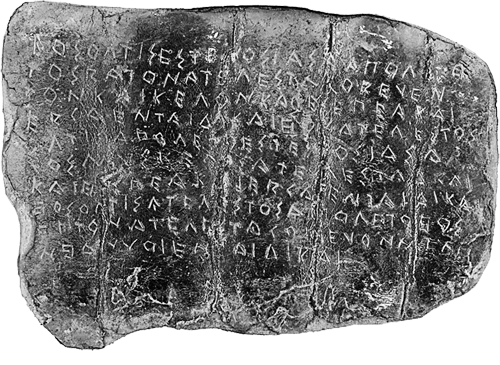

The hype surrounding the iPad made it the most famous tablet since the ones Moses brought down from his conference call with the Lord. Tablets – clay ones from the ancient Middle East – bear the earliest forms of writing that we know. So there’s something about the arrival of the tablet computer that gives you a feeling of the West coming back to some ancient dream of the future. It’s not hard to imagine an eighth-century Greek dreaming of a magic tablet that could, unlike the ones of wet clay he cut letters into and then dried, could have letters that rearranged themselves again and again.

Ideo, a firm that appears to be a sort of technology and design think-tank, came up with this video presenting some of their ideas on future possibilities for a tablet-based book.

The thing that stands out to me is that the functions described (social networking, intertextuality, interactive storytelling) are not so much new ones we’ve never heard of before, but are rendered visually in a straightforward, tactile way. It reminded me of another video, one which I saw a year ago with a proof-of-concept idea about the magazine of the future. I saw this early last year just before the iPad came out. Before its release, the device in the video seemed sort of incredible, and a few months later it’s no longer the stuff of the future. But the design problems introduced here will be around for a very long time, and are only beginning to be dealt with.

Media company Bonnier, the producer of the latter video, states this about their concept: “It has been designed for a world in which interactivity, abundant information and unlimited options could be perceived as intrusive and overwhelming.” That marks a distinct difference from the experience of reading on the internet, where even on a site that has a limited supply of content, the format itself doesn’t lend itself to a feeling that it is ever complete: ever finished, either by the site’s creator or by the reader.

I can find fault with the concepts in both videos, but they both are glimpses of something only beginning to be explored: how the unlimited options opened by a new technology will be shaped and channeled, made human in scale, and brought towards the simplicity and intuitive use that a printed book has. When you’re reading a good book, the book disappears and you’re in the world of language that the writer has crafted. We’ll know the digital tablet has matured when we’re no longer be excited by the tablet itself, but by what is being presented on it.