Late one summer night last year, a mountain lion stood in the parking lot of a vacant pharmacy on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley. The mountain lion might have looked up and seen a man framed in the yellow light of a window, watching. Soon after, Berkeley Police followed the animal down Cedar Street. They intended to chase it out of the quiet, residential neighborhood and into a park. The mountain lion vaulted a fence, vanishing into a dark and empty playground. Then it moved on, on a zig-zagging course through urban backyards. By now, the intentions of the police had changed. They encircled a home on Walnut Street, and in the backyard, an officer fired two shots—which missed. Moments later, in the driveway, a shotgun blast erupted, and the mountain lion was dead.

In the days after Berkeley PD exterminated the mountain lion, angry calls poured into the department. Why couldn’t the cougar have been tranquilized and relocated? Why did it have to be killed – what threat did it pose to humans? It’s true that in the long-term, mountain lion attacks on people remain extremely rare. Humans are the most dangerous animal in California, the apex predator. The 20th century nearly went by in California without a single human killed by a mountain lion. But there was one death, in the early 1990’s. Barbara Schoener, a 40-year-old rehabilitation counselor, was knocked from the trail on her morning run. When her body was found at the bottom of a ravine, it had been partially consumed. This took place on a trail near Auburn, where I lived at the time, and I remember people talking about it everywhere. It reminded them that mountain lions are, in fact, dangerous animals too. At least one question that came up then was being asked in the Bay Area again last year: how many mountain lions are out there?

“We don’t have any specific numbers,” said Patrick Foy, a warden at Department of Fish and Game. “Increasing, decreasing, or constant. In any particular geographic area, including the Bay Area.” Foy gave an estimate between 4,000 and 6,000 statewide. “That number has been used in the fourteen years since I’ve been at Fish and Game.” He said that the figure is drawn from the amount of mountain lions that the available habitat will support.

“Now, are there mountain lions in the Bay Area?” Foy went on. “The answer to that question is yes. A lot of people are surprised to know that.”

Mountain lions are indigenous to a wide swath of the Western US including much of California and the entire Bay Area. Los Gatos, the town my mother grew up in, gains its name from them, since they were long known to hunt the foothills in that part of the south bay. The vast areas mountain lions roam¬—a male mountain lion will roam from 50 to 300 square miles—are typically ones where few humans are found. No one really knows how many of the lions are out there.The determining factor is an environment where they can thrive. For cougars, that means deer, Foy said.

“Anyplace you find a plentiful supply of deer, you’ll find mountain lions.”

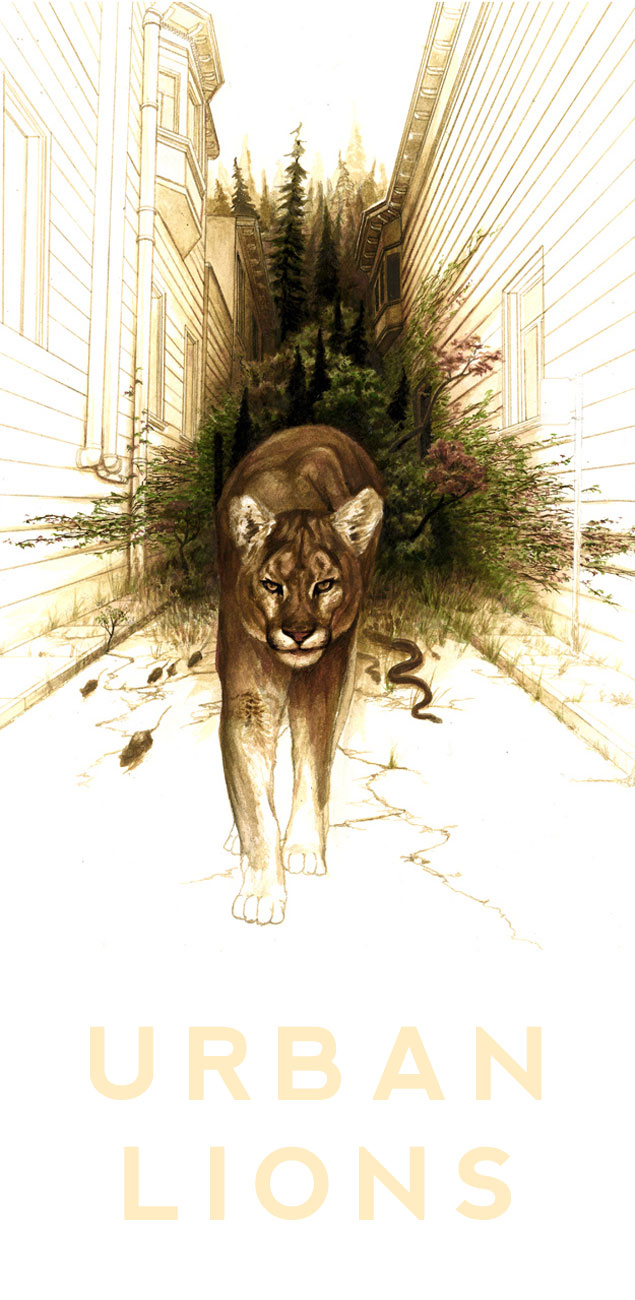

When I heard that a mountain lion, usually so solitary and reclusive, wound up in the City of Berkeley, I had to wonder: are mountain lions making a comeback after generations of human encroachment on their habitat?

“No,” Jim Hale said, “What happened is we had an extended rainy season.”

Hale, a wildlife biologist, explained that the distribution of rain through the spring and early summer had increased the biomass, despite it being a somewhat dry year.

“We had a lot of plant success, therefore that trickled all the way down through the food web and food chain. With increased biomass we had insects, all the rodent populations did well, gophers, mice, and all the way up from the mesofauna through to the megafauna. Smaller carnivores and coyotes; skunks and raccoons; raptors, eagles and hawks and falcons; and all the way up to the mountain lions. It was a really good year for wildlife.”

Hale felt that it was the abundance, rather than the scarcity of food, that had led a mountain lion out of its normal path and into an area highly populated by humans. In Berkeley it seems to have been the first sighting of a mountain lion in anyone’s recent memory.

“This was really the first I’ve heard in Berkeley,” said Marcie Burrell, an Officer at Berkeley Animal Shelter. “It’s really unusual.” Burrell said that she felt that the well-visited Tilden Park served as a sort of buffer zone between more remote areas the mountain lions use as habitat and the urban area of Berkeley.

A sidewalk memorial to the mountain lion appeared on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley, similar in style to the ones for murdered youth in nearby violence-wracked Oakland. One handwritten post on the shrine read “Let’s honor life by not killing wild animals. Instead, let’s protect and cherish them so rare and precious.” The following lines echoed the passage in Luke where Jesus asks forgiveness for his murderers: “Please forgive the ones who killed the mountain lion. They know not what they have done.” The mountain lion was, for this person, not just exterminated, but crucified. But the lion died for their sake only in the most literal sense, not in any cosmic one. The mountain lion is only innocent and pure in the same sense that a rattlesnake, or a grizzly bear, or a possum, or a wolf is. They’re beautiful, but they should be viewed as what they are: beautiful and wild, owing nothing to us or our moral sensibilities.

At the other end of the spectrum from the idealization of these animals into spirit guides and personal totems is the scapegoating and demonization of them. If the result of last year’s encounter between human and cougar in Berkeley had gone differently: if, say, in the hills in the East Bay or Peninsula a runner had been attacked like Barbara Schoener was in the 1990’s – public fear would most certainly be outweighing public sentiment towards the cats even in the ecologically-minded Bay Area. Despite the fact that accidents with asparin and air bags alone kill far more every year, when an attack occurs mountain lions are rarely viewed as a necessary risk to live with. In rural areas, cougars have been known to kill livestock and pets, sometimes “surplus killing” as many as 20 sheep in a single night. Backlashes have seriously damaged mountain lion populations.

“It was suggested there were as little as 600 left statewide back in the 1960’s, when there was a bounty on them,” said Jim Hale.

As we’ve seen, the numbers on how many are around today is hardly known.

In order to live in parallel harmoniously, long term, with the cats, the need for better information is obvious—especially as the Bay Area prepares to add over two million new residents in the next twenty-five years. A new 10-year study of the animals called the Bay Area Puma Project (BAPP) has been launched to respond to this need for information on mountain lion populations in the Bay Area.

“The main issue here really is about movement corridors for these cats to disperse and get out of human-dominated zones,” said Zara McDonald of the Felidae Fund, who is conducting the Puma Project along with UC Santa Cruz, and the California Department of Fish and Game.

BAPP’s info sheet notes an increase in depredation permits, which are issued to kill a mountain lion when it is deemed a threat (usually when it has killed pets or livestock), and tensions in local communities. The goals of the project are to increase awareness and support for preserving the natural balance that keeps mountain lion populations healthy.

As pointed out in an article on Bay Nature, despite the dozens of pumas killed under permit every year, California stands out for its protection of the cats. It’s the only state where hunting the animals for sport is illegal—and has been since the 1970s. And as the state with the greatest number of people and what some think is the largest population of mountain lions, the coexistence between us and our neighbor predators is one that, in the broader sense at least, works.

BAPP hopes to extend its studies to the East Bay in 2011. For more information, visit http://www.felidaefund.org/research/bapp.html