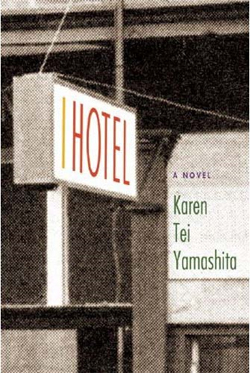

By Karen Tei Yamashita

640 pages

Publisher: Coffee House Press, 2010

The I Hotel, or International Hotel, was a residential hotel in San Francisco’s Chinatown housing elderly Filipino and Chinese immigrant workers, mostly bachelors. It was demolished in 1979 to make way for redevelopment. Karen Tei Yamashita’s novel I Hotel, a finalist for the 2010 National Book Award, is an experimental epic that spans ten years in the social and political activism of the San Francisco Asian community, and the stories it tells intersect with the history of the I Hotel. In the book’s afterward, Yamashita writes that the elderly workers were “men who had come to work and make their fortunes prior to World War II and who, because of anti-miscegenation laws, prohibitions on Asian immigration, and a life of constantly mobile migrant labor, were unable to find spouses, have children, and to settle in the United States.”

Yamashita not only covers the lives of some of these bachelors, but also those of young activists fighting against the closure and destruction of the I Hotel, forming what was then dubbed the Yellow Power movement, inspired by the civil rights, antiwar, Socialist/Marxist, and Black Power movements of the late 1960s and 1970s. Yamashita tells these often disparate tales through ten novellas, each covering a year from 1968, following the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, to 1979. A cast of characters spans the scope of the political and social events that occurred in the Bay Area during this period.

I enjoyed reading I Hotel for the most part. Some of the novellas and characters are quite compelling and Yamashita is at her best when she is detailing the cultural and generational differences within the various Asian communities in California (Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, etc.). She creates a milieu within the novel that is fully realized, bringing to life the cultures of Japantown and Chinatown in all of their complexities. Unfortunately, the novel’s strength is also its weakness, as it tries too hard to include too much. In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times last year, Alan Cheuse wrote that the novel was “a glorious failure of a book,” and I would have to agree. Yamashita makes the mistake that social realist novelists make in that she weighs in on the side of inclusivity, often at the expense of the story. At 640 pages the novel feels weighed down by repetition and narrative stagnation.

Yamashita spent ten years doing research for I Hotel. Unfortunately, it shows. She takes pains to include the voices of everyone during this time period, but not all of the narratives she includes are compelling enough to warrant inclusion. Some characters seem to exist merely to (re)present a type. Considering that the novel delves heavily into Marxist theory, perhaps Yamashita wanted to capture the collective struggles of a people and movement rather than pursue more artistic inclinations (Yamashita does set aside some time to introduce the argument over whether art should exist for its own sake or should exist for the proletariat, an argument she leaves to the reader to resolve). However, this only reveals the limitations of ideology over art. The most compelling characters in the story, such as Paul Wallace Lin, Chen Wen-guang, and Edmund Yat Min Lee, who appear in the first novella, are the most memorable precisely because their wants, desires, and backgrounds defy archetypes and ideological dogma.

Cheuse, in his review, claimed that the more experimental sections of the novel are the least successful, but I would have to disagree. Yamashita’s use of graphic novels, dossiers, screenplays, stage plays, and other formats is the most compelling aspect of the novel, offering critiques of Socialist/Marxist dogma and revealing how form changes and redefines representation of class, race, and gender.

In spite of its flaws, I Hotel is an admirable effort that looks at a period in American history through a unique perspective. To be honest, I wasn’t aware of a Yellow Power Movement, in spite of being born and raised in the Bay Area during this period. I Hotel preserves a history that is otherwise ignored in mainstream literature. The last twenty-six pages alone are a beautiful testimony to the voices of a people struggling to live, survive, love and thrive in this country. And Yamashita’s push toward experimentalism also offers hope in further breaking down the boundaries of what the novel can achieve. I Hotel may be a “glorious failure”—sprawling and frustrating—but it is a failure worth the experience.