Edited by Alix Lambert

352 pages

Publisher: Fuel, 2008

In her book Crime, Alix Lambert—photographer, documentarian, and writer for the sensational, phenomenal, transcendent and much-missed HBO series Deadwood—compiles a series of loose, free-flowing interviews all revolving around its title subject. With such a big, overarching topic it would seem easy for any book which seeks to chronicle it through firsthand testimony and oral history to veer off course and become somewhat unwieldy. And this is, indeed, what happens. But that’s okay! In this case it’s a good thing.

Less a thorough examination of crime through its impact on those who experience it firsthand, Crime is a free-flowing collection of associations. In many ways it recalls Michael Ondaatje’s novel-poem-found-artifact hybrid The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (which is mentioned at least twice by different subjects in this book). Like Ondaatje, Lambert is seeking for something more personal and yet simultaneously universal than the initial presentation of the book might imply. As she says in her introduction “This is not an unveiling of crime and art… rather, it is an unveiling of my own movement through thoughts about crime and art.”

Indeed, art and its representation of crime are a big part of the book. Interviewees include David Cronenberg, Viggo Mortensen, David Mamet, Elmore Leonard, Dennis Lehane, Ben Affleck, Samantha Morton, and Ice-T, among other actors, directors and writers. They tackle their experiences in creating work that deal with crime in its various incarnations: Cronenberg and Mortenson with Russian Mobsters; Affleck and Lehane with the working class Boston underworld; Mortenson on playing a notorious British child murderer. Mamet, Leonard, and Ice-T on, well, being fucking Mamet, Leonard and Ice-T.

Due to the free-wheeling nature of the questions, which are not presented in the text as questions but rather simply subject headers, they are free to go off on all types of other facets of themselves and their work. You suspect some very clever editing has gone on to make the responses well-constructed and smooth while still conversational and fluid.

Cronenberg details his early, almost picturesque Canadian upbringing where his earliest dalliance of crime came from stealing comic books from the grocery store. Mamet recalls the first crime he ever witnessed being a guy driving down a one-way street, and how he felt moved to tell a police officer he’d seen this, only to later identify his need to report crime to police as a personal defect.

Obviously, big names like Cronenberg and Mamet are the attraction for perusing potential readers, but lest you think the whole book focuses on artist’s interpretations, there are also plenty of interviews with people personally connected to or touched by crime—anonymous as the rest of us, but with incredible stories.

Private detectives, criminal lawyers, ex-convicts, still-incarcerated convicts, reformed British gangsters, and current Russian mobsters all make appearances. Los Angeles chief of police William Bratton pops up, as well as an operational undercover agent who goes unnamed. Through their testimonials we get just as much digression on early memory, as well as their take on the intersections between art and crime; but we also get firsthand accounts of their very close connections to real examples.

Especially moving is the testimony of the author’s friend Sarah Kennon, whose sister Melissa Ruben was brutally raped and murdered in 1987. She recounts the shock of that trauma, the stages of grief one goes through at the time as well as two decades later.

On the other end of the spectrum, Crime contains some chillingly casual descriptions of acts by those who perpetrated them, such as Seymon Dyanchenko, a Russian convict serving time for killing and beheading three men after they desecrated the grave of his recently buried mother (in his defense, they did kind of have it coming). Dyanchenko might have the line of the book:

“The third one begged me for mercy. I said, ‘Of course,’ and cut off his head.”

Crime gets into the minds of criminals and non-criminals alike, and lets them expose themselves thanks to it’s uninterrupted form and its merciful lack of moralizing or politicizing (not that some of the subjects don’t get into that territory). In the same way an Errol Morris documentary lets its subjects reveal themselves, so too does this book, whether it’s giving them enough rope to hang themselves, or allowing them to reveal a surprising revelation which flips the reader’s empathy to their side.

Lambert explains in her introduction that there was no checklist of subjects she had before she began the project. She would talk to someone who would put her in touch with someone else. Having done a documentary (The Mark of Cain) about Russian prison tattoos, one can see why she would be led to Cronenberg and Mortenson (or if one can’t, then go rent Eastern Promises right now). But then to see someone like Takeshi Kitano is a wonderful surprise.

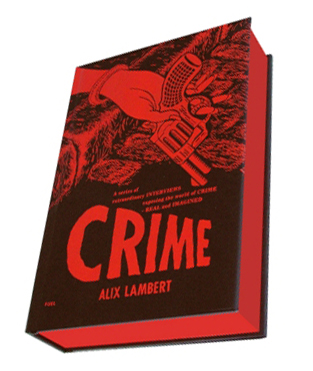

The book should also be credited for having a unique and very appealing aesthetic. Published through Fuel Press and destined to be a collector’s item, the red dye on the edges of the pages, along with its black bindings (replete with a perfect encapsulation of pulp art covers through a simple but evocative image) give it a forbidden and lurid texture, just as the photos inside by Lambert captures the personal, guard-down, contemplative nature of the text.

Although often crime is regarded as a genre, similar to science-fiction, fantasy or westerns, the truth is that crime weaves through so many factors of art—high-and-low—that it should be regarded as a prism through which we can view the human condition; like sex, race, religion and history, it intersects with all of our lives.

What is Oedipus Rex if not a crime story? Hamlet? Hell, Crime takes its epigraph from Dostoevsky (Crime and Punishment, of course; though Lambert could have just as easily used House of the Dead or The Brothers Karamazov). If you are interested in the human condition, whether you prefer Dostoevsky or Elmore Leonard (and who’s to say, taste-wise, that they’re mutually exclusive?), you owe it to yourself to pick up Crime.

It’s an experiment more than anything definitive, true, but if only all literary experiments were as entertaining and beautifully presented as this.