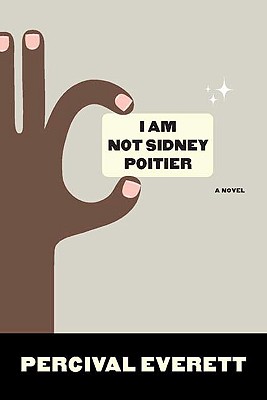

Author: Percival Everett

Paperback, 272 pages

Publisher: Graywolf Press, 2009

Author of seventeen novels in just over twenty years, Los Angeles-based author Percival Everett is what you might call an inveterate workman, always flying just under the radar of the broader recognition which most of his readers would agree he deserves. He made some noise with his 2001 novel Erasure—a scathing, savage bit of satire which set its sights on the publishing industry and the relationship it has to black authors—but after that his books met with a quiet reception. That seems to have changed with the publication of his latest, I Am Not Sidney Poitier, released last year to wide critical acclaim, and subsequently winning the 2010 Believer Book Award; it seems that this may be the book to firmly establish Everett as one of the major voices of modern American fiction.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier is a comic picaresque along the lines of Bellow’s Adventures of Augie March, though with its relatively short length and sparser style it doesn’t have the breadth of that novel. The wild turns of the plot give it an epic quality that is set against the stoic, patient tone of its first-person narrator. The character at the core of the novel is a stroke of genius from Everett: an amiable young man named Not Sidney Poitier (no relation to the famous actor). Orphaned at eleven after the death of his eccentric, but possibly brilliant mother, Not Sidney is whisked off to Atlanta by none other than Ted Turner, in whose burgeoning media empire the late Ms. Poitier had been an early and heavy investor. Not Sidney grows up in a mansion next to Turner, wealthy beyond belief, and seen to by a house full of servants.

As Not Sidney grows up he struggles with several crises of identity as he considers his ethnicity, social class, family, and even the possibility of the supernatural. His mother claims he was the product of a virgin birth, and eyewitness testimony holds that he had been in the womb for almost twice the average length. At an early age he learns the secrets of a type of on-the-spot hypnosis which he uses to ward off enemies, to effects both successful and disastrous. Then there is the uncanny resemblance he bears to the actor of his anti-namesake, which is exacerbated as he finds himself falling into adventures that bear an uncanny similarity to the actor’s most famous films. Arrested for “driving while black” along the back roads of Georgia, he’s put on a work farm, only to break out while chained to a country bumpkin. After forming his first relationship with a young woman he is taken to her home for Thanksgiving, only to discover that her light-skinned parents don’t appreciate their daughter dating someone dark-skinned. Later he encounters a sect of fanatical nuns who claim that God has sent him to them in order to build a church, and while embarking on this latter endeavor, he gets roped into helping a local Sheriff solve a murder that he is originally accused of. None of these misadventures resolve themselves the way they do in the films they’re based on. Everett uses them as springboards to dig deep into the American psychosis of race relations in ways messier, funnier, and in some cases darker, than the films Mr. Poitier appeared in.

Not Sidney, though often flabbergasted by the insanity surrounding him, is a pretty passive protagonist, to the point where it can be maddening. This is by design. Not Sidney is, like Bellow’s Augie March, a young man adrift in a world where high importance is put on one’s social status. His name makes Not Sidney a kind of avatar for the idea of the modern (or postmodern) African American male, and he seems to be sculpted in direct response to the confusion that has spread since the election of Barack Obama, where no one is really sure what we mean when we talk about the “new” black American experience. If, before Obama, Sidney Poitier was the standard-bearer for proud assimilation of black males into the American mainstream, then how is someone like Not Sidney—who is named in opposition to that ideal yet who himself has no aggression towards it—supposed to be defined? Considering the chaos that constantly seeks him out, the point Everett seems to be making is that self-definition is useless in the long run, and that people only get a true sense of their character when they are thrown head-first into drama. By the end, however, Everett also seems to be hinting at the possibility that we’ve gotten so confused by our ideal image versus our lived one, that there is no separating them at all.

As weighty as the themes and subtext of the novel are, it zips along with lightning fast speed, thanks to Everett’s clean, unpretentious style. It’s a truly enjoyable and fun read, helped greatly by the cast of supporting characters. Foremost amongst them is Ted Turner. In the novel, he’s a comedic figure thanks to his rambling and easily distracted nature, but is presented as a sweet and caring person with a deep reserve of dignity. There is also the author himself, one Percival Everett, who turns up as a college professor of Not Sidney’s and serves as a mentor of sorts. I say ‘of sorts’ because Everett has himself teaching a course entitled Nonsense 101, and that’s about all he’s capable of giving, in terms of advice. When, eventually, Turner and Everett meet, its a match made in head-slapping heaven. There’s also the assortment of racist Southern cops, crazy nuns, sexually predatory high school teachers, self-hating black conservative grotesques, and even a rambling, self-indicting Bill Cosby.

If these descriptors of the characters strike you as stereotypical, that’s half the point. By amping up the various caricatures we Americans have come up with for ourselves, Everett is able to explore his major theme: how much do our actions and internal lives define our identity, and how much does our identity define our actions and internal lives?