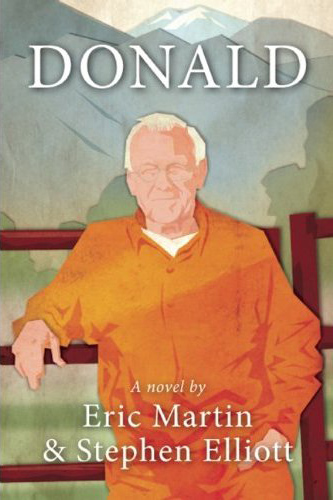

By Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott

Softcover, 112 pages

Publisher: McSweeney’s, 2011

In Donald, A Novel, which imagines what would happen if Donald Rumsfeld were imprisoned in the same harsh and secretive detainee system that he helped establish, there’s a scene in the first chapter that hints at what’s to come. In it, there are a few startling lines and insights, but overall it feels rushed and lacking. Our hero, former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, is in a library doing research for the memoir he’s writing. He’s confronted by two twenty-somethings, a boy and a girl, and he has an elliptical, ominous conversation with the boy, who tells him that he will have to atone for his (mis)deeds.

After getting a read on the boy as soft and inexperienced, Donald looks at his companion and thinks: “There’s a little war in the girl. Maybe from her father, or maybe because every beautiful girl has glimpsed the natural state of man, at least the part that would rape her if it could.” That’s a brutal line, and it gives the reader a look into the paranoid heart of its protagonist. Although there are a few examples throughout the novel where the writers, Eric Martin and Stephen Elliot, almost capture that kind of honesty again, they mostly lose it in the muddled story.

The book charts Donald Rumsfeld’s descent into a hell of his own creation, as he is abducted from his home and shipped to various secret prisons, where he’s put through the wringer of “enhanced interrogation techniques” that have become synonymous with the Bush administration’s “War on Terror” policies. It’s hinted that he’s accused of having colluded with terrorists, but the details are intentionally murky and he’s never formally charged with a crime (appropriately, given the policy of indefinite detainment pioneered during Rumsfeld’s tenure).

Over the course of his fall, he mostly remains the same character he started out as; though there are a few times he buckles, he never truly breaks. Donald, on the whole, is presented as part brute realist, part old-school romantic and man’s-man, part affable smart-ass.

There are several factors that keep the novel from working. The first is that rushed feeling, evident from the opening chapter. Donald is an incredibly slim novel, coming in at 112 pages, and was released by McSweeney’s on the same day as Donald Rumsfeld’s actual memoir, Known and Unknown. Though the novel doesn’t come off as a full-on stunt, as the publicity behind its marketing might lead one to believe, it doesn’t feel like a fully fleshed out piece of literature either.

It feels like a project. A project which the writers and researchers—McSweeney’s interns gathered research on Rumsfeld, as well as material on the detainees of the “War on Terror”—were sincere about, but a project nonetheless. The writing is appropriately cryptic for the dislocation of the novel’s themes, but it also has a tendency to switch to a distracting second person voice at times.

Publisher McSweeney’s describes the story as a “high-wire allegory,” as well as a satire, but neither description feels apt. To what is this allegorical? The character of Rumsfeld is Rumsfeld; the prison system he goes through is the prison system of the real world. When things start to break down at the end the reader is left as unsure about the state of the world as the character of Donald, but it doesn’t seem like the writers have a concrete answer to what’s happening either. It feels like a kind of Beckett-lite wasteland. If it’s an allegory to anything, it’s an allegory to the state of its fictional character’s mindscape.

This leads to another problem with Donald, which is of the representation of the eponymous figure at its center, Mr. Rumsfeld himself. Here we are given a man of immense hubris and overcertainty. He falls victim to the system that he helped put in place, and though he clamors about his innocence, blaming his imprisonment on either a mistake or liberal revenge, he never comes to doubt the worth of the system itself, which he insists is necessary for keeping the vast majority of innocent people safe. He maintains that level of inherent decency throughout the book.

This is a problem because that’s not the Donald we know. If there were cutting satire at the heart of this novel, one that did more than simply reaffirm the belief that the industry of false imprisonment, torture and lack of representation in the “War on Terror” is wrong, then maybe a dignified Donald Rumsfeld would be a character worth putting up with.

As is, what this book could really have used was a little bit of smart, blistering, liberal revenge. Co-author Stephen Elliot, in an interview with Galleycat, expressed his intention to make Rumsfeld a sympathetic character, and the evidence of the attempt is distractingly apparent throughout the book. Beyond the resolve he shows in the face of his brutal treatment, Donald is also shown as an intensely loyal and devoted family man, as well as a true patriot.

I’m not saying that Donald Rumsfeld isn’t those things—he may be. But it strikes me as odd that nowhere in this book do we find the arrogant, shifty, entitled asshole we saw Donald Rumsfeld to be time and again, in press conferences and interviews, throughout the Bush years.

Ultimately, Donald is never as savage as it should be in its portrait of Donald Rumsfeld. If it soared on an aesthetic level maybe that wouldn’t matter so much, but with the exception of a few cases, it doesn’t take off. The authors’ determination to show us the Donald Rumsfeld we don’t know—perhaps due to their liberal notions of fairness—places a large safety net beneath the “high-wire allegory” of Donald, A Novel. It would be a riskier—and better—book without it.