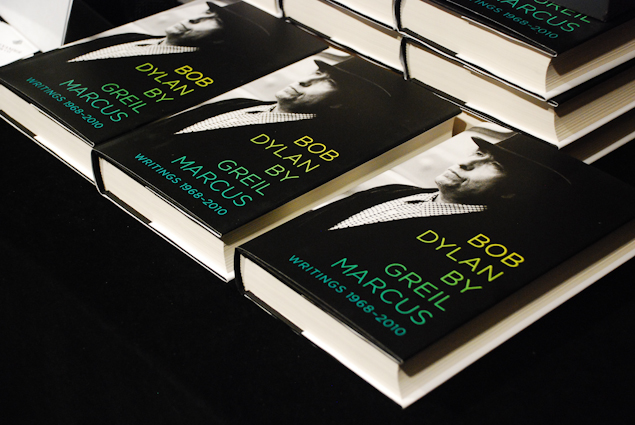

One of the Bay Area’s longtime cultural commentators and critics, Greil Marcus, has released a new book on Bob Dylan’s music: a 512 page volume collecting four decades of writings on Dylan’s work and the music and the times that influenced it. Marcus appeared at the Mechanic’s Institute last Thursday to speak and sign books. The author of The Believer’s “Real Life Top Ten” column and a former writer for Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and Artforum, Marcus has long been documenting American cultural history. His books include many on music and musicians, including Elvis, Van Morrison, and two on Bob Dylan prior to this one (which is titled Bob Dylan: Writings 1968 – 2010). Marcus is known for combining music journalism with literary history, placing songwriters and their songs in a broader context.

He began by describing the first time he saw Dylan, at a Joan Baez show in New Jersey in 1963. Dylan was “hunched over, covered with dust,” a slouching gypsy whose song “With God On Our Side” shook and startled Marcus, who described the song as a counternarrative to the American history taught in the 50’s: a steady progression of victories for democracy, victories for the nation “with the better idea.” Dylan retold that narrative, step by well-known step, but infused it with suspicion, with a deep sense of doubt.

Five years later, Marcus began writing for publication. It was 1968, Marcus was majoring in American Studies at UC Berkeley (where he now teaches), and the underground press in the Bay Area was very active. There were a number of “places where anyone could get published—send it in and they’d print it,” including the San Francisco Oracle, San Francisco Express Times, Berkeley Barb, and the early, then San Francisco-based Rolling Stone, which Marcus began writing for regularly. A dedicated fan of Dylan’s music “to whom no one’s work was as thrilling and fascinating,” he reviewed albums and concert appearances, and kept doing so even when he found himself forced to take a critical approach if he was to remain honest as a commentator.

Marcus then read excerpts from the book, first a scathing review of Dylan’s 1985 album, Empire Burlesque. “You hold a mirror up to the mouth and it clouds over – barely.” Marcus described how audiences and Dylan himself once took the music more lightly, earlier in his career, (the folk period) and how he “was a better rocker as a folk singer” – rooted in history and rooted in the present, but by the time of Empire Burlesque, rooted in nothing.

Marcus then read an evocative profile of Doc Boggs, a musician who was one of Dylan’s biggest influences. A former coal miner in Appalachia, Boggs was “rediscovered” in the 1960’s by young people in the folk scene. Boggs forged, Marcus said, a “distinctive and uncanny langage,” as singer of mountain songs and murder ballads. Marcus described wishing, as he wrote this: Dylan, this was one of your favorite singers, why don’t you go back and listen to Doc Boggs?

Then Marcus skipped forward, to a moment when he felt Dylan took a turn for the better as an artist: the album Love and Theft in 2001. Marcus’s review, unconventional and stylized, describes “an old man who lives in your neighborhood, drinking away his days as if they were bottles,” his house filled with a motley assortment of old and new objects.

Marcus asserts that a whole era of Dylan was a purposeful attempt at alienating or distancing himself from the public, citing the album Self Portrait (which Marcus regards with undisguised loathing). Even Dylan’s religious conversion was an attempt to ward off questions, Marcus said, adding that though he didn’t think the conversion was phony, it was a response to the microscope Dylan was living under: people were literally rooting through his garbage looking for clues to some deep and hidden meaning he was supposed to be privy to as the icon and messenger of a generation. Marcus described how he’d thought of Dylan when reading John Berger’s book The Success and Failure of Picasso. There was a point at which an artist—even, and maybe especially, a successful one—no longer had a subject, a need to make their art. Marcus thinks this moment, for Dylan, lasted for some 25 years.

During the question and answer session, several in the audience revealed themselves, with self-effacing humor, to be Dylan obsessives themselves, and shared stories of the meaning of Dylan’s performances and songs in their lives, and common thread in the stories and the questions was the time: how the songs were felt to embody the time and place, a special and rare time that had slipped away along with youth and innocence. Marcus responded with a touch of helplessness, saying “we’re bound up with this character.”

His latest examination of Dylan’s work won’t be for everyone: it’s clearly an exhaustive approach that revels in minutia and opinion, perhaps as much about Marcus’s perspective on American culture as about Dylan. But given his length and breadth of meditation on the matter, for those who are bound up with Bob Dylan, the book will be a welcome addition to the literature on this artist.