A Conversation With Manuel Muñoz

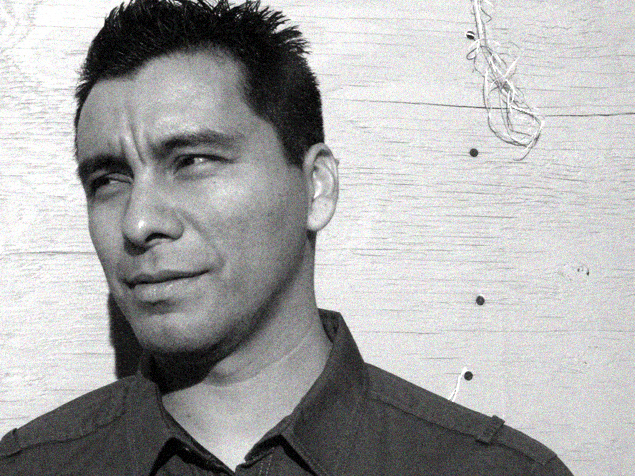

Manuel Muñoz, author of The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue and Zigzagger, does for the Central Valley what John Steinbeck did for the Salinas Valley. His tales about migrant workers and their families, dreaming of better lives and expressing their sexual identities in a conservative environment while caught in the cycle of poverty and poor choices, are clear-eyed and unsentimental depictions of a way of life few people outside of the Central Valley are privy to. His latest novel, What You See in the Dark, juxtaposes the hard-scrabble lives of the people of Bakersfield circa 1959 with the glamor of Hollywood just as filmmakers were pushing to make the cinema more “realistic.” Now residing in Tucson, Arizona, where he is an associate professor, Mr. Muñoz is hard at work on his next writing project. I had the pleasure of conducting an email interview with him about growing up in the Central Valley, his influences, and the movies.

In your bio, you state that you’re from Dinuba, California, home of Odwalla juice. In what way does your upbringing in the Central Valley affect your work and sense of place?

I left the Valley when I was eighteen years old, though my entire family still lives there and I visit them frequently. The Valley is such an integral part of Chicano history, yet its representation on the page has been relatively scant. I suppose my commitment to representing it has increasingly less to do with place (write what you know!) and more to do with an understanding that the lives of the people who call the Valley home are just as intriguing as anyone else’s.

Is it a desperate place? Yes, but writing about it isn’t about rubbing the nose of the American reader in the muck of poverty. It’s a call for compassion, a way to personify the lives of people who are very often crassly vilified or dismissed.

What inspired you to write What You See in the Dark and how much did growing up in the Valley prepare you to better understand the cultural and political changes that were affecting areas like Bakersfield during the 1960s?

I love old films, and I love them in particular because they provide a terrific opportunity to study how social attitudes made their way into art—the hesitations, the daring, the bravery, the timidity, etc. Watching old films also reminds me of just how much American art has changed: to see Charlton Heston play a Mexican cop in Touch of Evil is laughable, but it also reminds me of how closed and exclusive the world of film was to non-white participants.

The Valley is a place in which all the tension of social clash is underneath the fabric of the community. With the exception of the UFW marches in the 60s and 70s, major pushes for political change remain the domain of the big cities. I’ve always seen the Valley as a place of observers: if you’re not watching the neighbors, you’re watching the news, waiting to see how what happens next door or in the big cities will change your life. It’s a place of reaction, rather than action. It makes change slow to arrive.

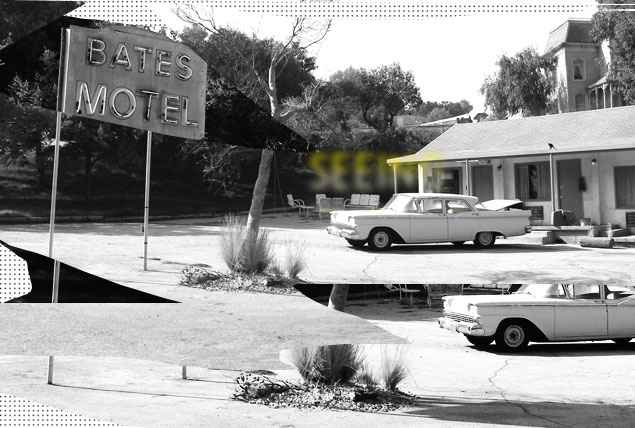

Death and the way it is depicted in film is a thread that is woven throughout your novel. And yet you chose not to depict Teresa’s murder. What led you to this choice and how much has the film Psycho influenced the way you think about death and violence as it is ritually performed in popular culture?

Depicting Teresa’s murder required choosing a point of view. I tried writing the last chapter from both Teresa’s and Dan’s point of view. What I came up with was some very brutal writing. Both points of view seemed a rebuke to my own argument that death in film generally required a removal of any kind of humanity—the body is a prop, not a person—and I saw this happening in my last chapter. With Teresa, the POV choice seemed almost pornographic. With Dan, I worried that the POV choice hinted at a pleasure in depiction. I found myself become more and more convinced that film really gets away with something as an art form when it comes to depicting death: the camera can play observer only, distant and therefore uninvolved.

This was the reason I finally tried the second person and attributed this “you” to a specific character in the novel. By making the murder one that is imagined (because no one in the town actually witnessed it), I was able to “depict” the murder and ultimately offer the chapter as a comment on our desire to witness this kind of brutality. The character behind that “you” is key.

You have a very cinematic writing style. How much has film influenced you as a writer? Are there any movies that have had a particular impact on you in terms of style and tone?

I’ve heard “cinematic” since my undergrad workshops days. I think that’s because I tend to privilege details over anything else. I like to set the stage in order to ground the characters in a particular space. The accumulation of detail, I’ve found, contributes tremendously to tone: it forces attention and highlights when and how the character finally “moves” (since my characters tend to think more than act). I like the challenge of producing work that values character interiority, yet still gets a reader to use that word “cinematic” in describing my style.

The films I love tend to be the ones with visual fluency, made by directors with marvelous eyes for “shots.” I’ve written often about Robert Altman and love the narrative possibilities of his multi-character films. But what I love most are the small moments: the shot of the blood-stained tile in the apartment stairwell at the closing of Taxi Driver, for instance. Or the quiet faces of the audience as they watch Sissy Spacek break down onstage in Coal Miner’s Daughter. Or Lillian Gish blowing out the candle in Night of the Hunter. Watching moments like that inspires me to focus on the details that would be required for me to describe it via text. I often use them as a challenge: how could I describe that, I ask myself, in the fewest sentences possible?

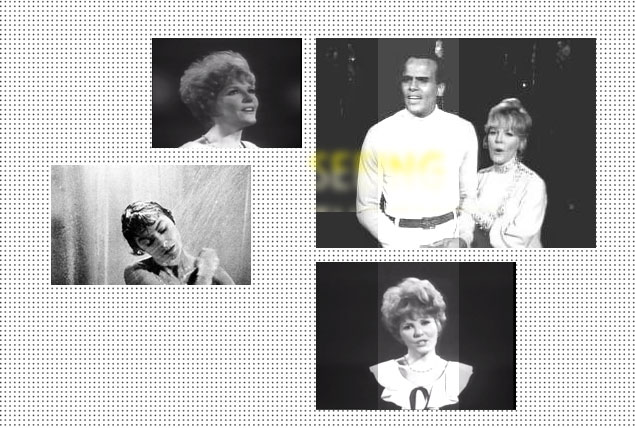

You use Psycho and Harry Belafonte’s TV appearance with Petula Clark as two pop cultural events that signified the eruptions going on in 1960s America. In a decade where so much was happening culturally, what made you consider these two as opposed to other more well-known moments?

I think Psycho is a no-brainer. Its genius resides in the very fine line between showing everything and showing nothing. Subsequent movie violence couldn’t rise to its level because later scenes couldn’t match Psycho’s apparently indifferent camera. I think that’s why movies, more or less, completely embraced the gore almost from the get-go. Since it’s too hard to stylize violence and make the moment truly horrifying, it’s simply easier to joke about it.

The Petula Clark moment was a lucky accident. A moment in the novel required the song “Downtown”: I was thinking about the lyrics, and what they would mean to someone in Bakersfield. This is something that is important to me: how democratic is art? When we say we “relate” to something, what the hell are we talking about? On those simple terms, a song like “Downtown”—which advises me to forget all my troubles and forget all my cares—means nothing in a place like my hometown. So where is the pleasure in that song coming from?

The more I latched on to the song, the more I kept listening to it. I went on to YouTube and found a Petula Clark variety program which, strangely, didn’t even have her sing “Downtown.” That’s how I found out about what the Harry Belafonte moment had meant to the producers of the show and the uproar created over Petula Clark touching Belafonte. I hardly even noticed it, but when I read the account over her refusal to reshoot, I knew I had hit upon a moment that was very much like a movie: one goes in with a particular expectation (I’m about to see something!) but our imaginations tend to be more powerful than the actual image. Petula Clark’s refusal to reshoot seemed, to some, that her touching was inappropriate. But how? One could only find out by watching.

Incidentally, this was made all the more fascinating to me by video footage of Sidney Poitier winning an Oscar. It is handed to him by Anne Bancroft, and the moment occurred several years before this on what is arguably the biggest entertainment stage of all. I recommend watching.

You mention that Helena María Viramontes is a mentor of yours. In what ways does her work influence your own?

We have radically different styles, but her mentorship was always about me. Her first order of business has always been to tell me what my work is doing—not what she wants it do, as a reader, but what I’m doing as the writer. That’s incredibly hard to do, but my god, how generous! It respects me as the writer and the hard work behind the draft. She taught me to speak up for myself. This is the way I teach now, and I do it this way because it promoted my self-confidence when I was a student. I couldn’t explain what I was doing on the page and was reluctant to do so. She made it okay to openly state my ambition on the page without any fear of ridicule. She taught me that my instinct was more valuable than anything.

Also, she’s an incredible reader. I was in Ithaca when the National Book Award nominations were announced one year and Bonnie Jo Campbell’s American Salvage was one of the finalists. It was a Wayne State University Press book, so the inclusion of a small-press title caught the publishing world by surprise. Helena had already read it. When I asked her how she found it, she told me simply, “It was at the bookstore. It sounded fantastic.” She has such curiosity, such openness about what literature can offer. I wish more readers (and even more writers) were like her. Too often, people can only talk about what a book lacks, how it failed. When I picture Helena with a book in her hand, it’s a positive image: “Isn’t this wonderful?” Her attitude reminds me that most writers work very hard and with integrity, and that it’s important, as readers, to answer them with an open mind.