This year, Burning Man sold out. Not in any metaphorical sense (that’s a debate of its own), but in a literal one: all tickets were sold in advance of the event, a first in the history of the annual festival—which is currently in full swing and will peak on Labor Day, when “The Man” will be torched in effigy, spiraling flames into the desert sky.

This year, Burning Man sold out. Not in any metaphorical sense (that’s a debate of its own), but in a literal one: all tickets were sold in advance of the event, a first in the history of the annual festival—which is currently in full swing and will peak on Labor Day, when “The Man” will be torched in effigy, spiraling flames into the desert sky.

It’s a significant year for Burning Man, the festival that has grown into a city—Black Rock City—that is erected and then dismantled every year in the Black Rock desert in Nevada. Along with record ticket sales, Black Rock LLC, the company that operates the festival, is proceeding with plans to transfer ownership to a nonprofit organization that will then administer the event.

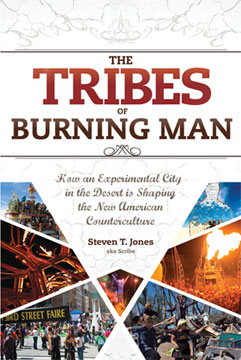

It’s also a big year for Steven T. Jones (aka Scribe) a veteran political journalist at the San Francisco Bay Guardian: his book The Tribes of Burning Man: How an Experimental City in the Desert Is Shaping the New American Counterculture was recently released.

It’s one of the most comprehensive histories yet of the event, which began over 20 years ago with an Ocean Beach bonfire. Jones weaves in his own relationship with the festival, which he first visited during the turmoil of the Bush administration. His book takes the reader from his speechless awe at first encountering the participatory art extravaganza, and on to a detailed examination of its origins and the issues raised through its history.

The personalities and politics behind Burning Man are rich material for exploration, and there is more than enough drama to go around, including legal battles and settlements between the founding organizers. As Jones relates, Burning Man “sold out” long ago, according to some of those closest to it, and many of the core creators want nothing to do with the happening they helped into being, one that continues to attract interest and participation and balloon in size and popularity.

The still-unfolding history of Burning Man resembles, in some ways, the story of other countercultural movements—punk rock, for example. A statement of revolt and nonconformity by a small group becomes, in the eyes of those who started it, quickly diluted and co-opted as it grows in size and attracts more participants. The question of who Burning Man belongs to has been an ongoing debate, often cast as a clash between the so-called “Borg” (Black Rock LLC, long run by founder Larry Harvey) that makes the city run and the “burner” participants without whom the event has no soul or purpose.

The internal debates of Burning Man’s history as outlined in The Tribes of Burning Man illuminate many of the inner workings of the event, and what makes it tick. For example, the percentage of ticket revenue which is awarded to artist projects as grant funding. Burning Man artists have complained the process was too complex, and the percentage of total ticket revenue devoted to art was not large enough—Black Rock LLC countered this by arguing it was already a far simpler grant process than in the mainstream art world. There is also the tremendous overhead in running the basics of Black Rock City, which includes inspecting all art projects for safety (fire, darkness, and 80-mile-an-hour winds present some serious challenges).

At a book release some weeks ago at The Booksmith in the Haight, Jones found himself facing charged questions from some of those in attendance, cast somewhat uncomfortably into the role of expert and interpreter of a happening that is both difficult to define and to pin down. Questions ranged from the very basic “why do people do this,” and “how does it work” to the more philosophical question that Jones mulls over in his book: is the tremendous energy, resourcefulness, and creativity expended on this massive counterculture event best spent on Burning Man, or would it be better put to use transforming society, resisting war and other injustice, in a more permanent way? Is it all just self-expression for the sake of itself, and isn’t that self-indulgent?Jones clearly believes that having a safe and free space where people are able to let their freak flag fly—to be naked if you want to be, queer if you are, forgetful of all workaday cares, and if you’re so inclined indulge in some mind-expanding chemicals—is valuable in itself. But his focus on what he calls the “tribes” of Burning Man is, in a way, a response to the “why does it matter” question. Outside the annual convergence of Black Rock City, there are countless regional groups (most densely clustered in the Bay Area) of burners organized around everything from art cars and welded sculpture to electronic music to the revival of circus arts like trapeze and mime. Tribes makes the case that these Burning Man-aligned affinity groups have real social value and connect like-minded people who otherwise wouldn’t have the same bond.Jones’ strongest example for the broader significance and good that comes from Burning Man is a group called Burners Without Borders, started by Tom Price in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005—which hit New Orleans during the Burning Man event. Jones heard of their work and then traveled to Mississippi to witness it himself. The group tapped its network of Burners to provide disaster relief and raise funds, some of them traveling to the Gulf Coast to apply their ethos of radical self-reliance and civic-mindedness (two of Burning Man’s “10 Principles”) where help was badly needed. They succeeded in providing an estimated million dollars worth of volunteer demolition and debris-clearing, as well as other projects—including working with Islamic Relief and the Salvation Army with materials from the Mormon Church to help a Vietnamese fishing community in Biloxi rebuild their Buddhist sanctuary. The Tribes of Burning Man is full of such unlikely meetings at the crossroads, and one gathers that facilitating those kinds of encounters is one of the biggest reasons Burning Man continues to exist, and keeps people coming back.

The Tribes of Burning Man also chronicles how closely Burning Man’s history is interwoven with Black Rock City’s civic parent, San Francisco. And now-unfolding developments indicate that Burning Man may, in one sense, be coming back home. In a recent article in the SFBG called “The Future of Burning Man,” Jones wrote that the Burning Man Project, the non-profit organization preparing to take over responsibility from Black Rock LLC, is looking towards a “future that has as much to do with San Francisco as it does Black Rock City.” The Burning Man Project envisions “a high-profile Burning Man Urban Center in San Francisco and other year-round facilities for furthering the burner culture, made possible by new funding streams.”

As Burning Man grows and changes, Steven T. Jones’s text provides some encouraging hints at what’s to come: a messy and contentious process that nonetheless has managed to bring together a dizzying array of creative people across mediums to make something unique in the world.