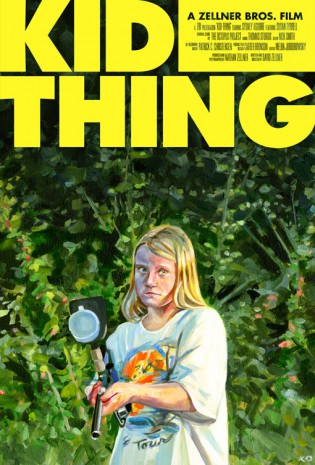

“There’s so much at Sundance,” said Cinefamily Director Hadrian Belove, “That a movie has to be really something for me to bring it here.” He explained that latch-key kid stories are close to his heart, and an audience member shouted “Home-Alones,” in reference to programming from Cinefamily’s baby years. Belove stood next to David and Nathan Zellner, who premiered their film Kid-Thing to 2012 audiences in Park City. I had the pleasure of listening in at the Bros.’ Q & A, and to speak with them after the screening.

“There’s so much at Sundance,” said Cinefamily Director Hadrian Belove, “That a movie has to be really something for me to bring it here.” He explained that latch-key kid stories are close to his heart, and an audience member shouted “Home-Alones,” in reference to programming from Cinefamily’s baby years. Belove stood next to David and Nathan Zellner, who premiered their film Kid-Thing to 2012 audiences in Park City. I had the pleasure of listening in at the Bros.’ Q & A, and to speak with them after the screening.

One reviewer likened Kid-Thing to “‘Days of Heaven’ on paint fumes,” but for the most part, it’s been met by lukewarm reviews. The LA Times’ Gary Goldstein jabbed at the film’s coherence, calling it a “minimalist, rule-breaking exercise in head-scratching human behavior.”

While the majority of human behavior could be considered “head-scratching”, what Kid-Thing addresses is that particular place in time where where we haven’t quite learned what we should do, and whether we’re going to do it or not. This is a film where ambiguity is the name of the game. I wasn’t even sure if the protagonist, played by newcomer Sydney Aguirre, was a boy or a girl for the first ten or fifteen minutes of the film.

She’s a girl—a ten-year-old named Annie, who roves around rural Texas in the same aerosol-can-painted-t-shirt day after day, breaking toilets, squishing grubs, gnashing lollipops, and generally being destructive. While Annie does her feral romp, antagonizing the few other children she encounters, her father-figure Marvin (played by Nathan Zellner) performs poorly as a goat farmer, hangs out with his (Vietnam vet?) buddy (played by David Zellner), and sleeps. The form of neglect that Annie experiences steers clear of more blatant physical or sexual abuse—a deliberate choice by the Zellner Bros, and one that fuzzies boundaries between natural childlike curiosity and sociopathic behavior.

The Zellners succeed tenfold in evoking non-sensical childhood vignettes, the ones without forethought or hand-washing. Something from far away clicks into place when you watch a bug-eyed ten year-old staring intensely off into space while gnawing off hunks of a technicolor lollipop, and moments later ferociously gutting a rotted log. These frequent “kid-thing” moments in the film are sometimes-joyful reminders of just how commonplace absurdity, non-sequiturs and unfinished tasks are in young life.

The Zellners succeed tenfold in evoking non-sensical childhood vignettes, the ones without forethought or hand-washing. Something from far away clicks into place when you watch a bug-eyed ten year-old staring intensely off into space while gnawing off hunks of a technicolor lollipop, and moments later ferociously gutting a rotted log. These frequent “kid-thing” moments in the film are sometimes-joyful reminders of just how commonplace absurdity, non-sequiturs and unfinished tasks are in young life.

As the film gains momentum to a buzzing and bursting score from The Octopus Project, Annie’s “gentle” destructions give way to more serious matters when she encounters Esther, a disembodied voice (performed by the late Susan Tyrell) in the bottom of a well. Annie’s rather cautionary approach to this trapped entity (“How do I know you’re not the devil?”) is a sharp reminder that human perspective takes years to be shaped and learned, and the naivete of youth does not equal commonly held ethical understanding.

To murky the waters further, the Zellners used “extremely simple sound techniques” to question whether Esther really exists at the bottom of her hole. None of the objects Annie tosses down, from sandwiches to walkie-talkies to firecrackers, are heard hitting the bottom. A mythical woman in the forest, often an evil one, is a common device in fairy tales, and the Bros. made sure to mention that such archetypal fables often conceal much darker themes.

During their Cinefamily Q & A, the Zellners noted that they had been approached by plenty of psychologists with comments on sociopathic behavior. An older, affluent audience was upset en masse that the protagonist was a girl and not a boy, and many of the German audiences during European touring were concerned with the film’s relation to Americana and American disillusionment. The general consensus seems to be that Kid-Thing is dark and disturbed. I won’t argue with that—it is dark—but its darkness should by no means obscure its pleasurable and anti-saccharine revival of kid-thing days.

During their Cinefamily Q & A, the Zellners noted that they had been approached by plenty of psychologists with comments on sociopathic behavior. An older, affluent audience was upset en masse that the protagonist was a girl and not a boy, and many of the German audiences during European touring were concerned with the film’s relation to Americana and American disillusionment. The general consensus seems to be that Kid-Thing is dark and disturbed. I won’t argue with that—it is dark—but its darkness should by no means obscure its pleasurable and anti-saccharine revival of kid-thing days.

Maybe the symbols are tangled, and maybe the conclusion leaves you hungry. Isn’t being a kid a bit like that? Sometimes ambiguity smacks of pretension (Is the green I see the same as the green you see? How will we ever know?), but Kid-Thing uses it to sharply, and artfully, remind us of childhood’s peculiar relationship to the fine line between innocence and moral void, imagination and reality. Isn’t that enough?

View the trailer here: