A Conversation With Alix Lambert

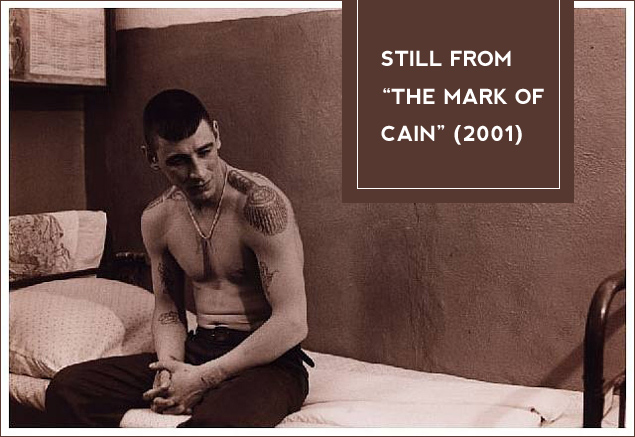

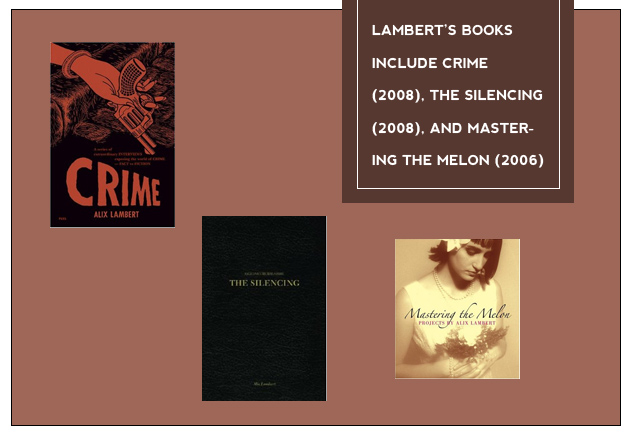

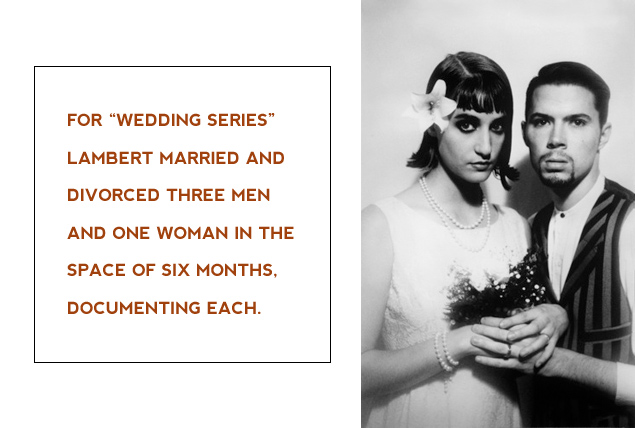

Alix Lambert’s work has taken her across many mediums—among other things, she’s a journalist, television screenwriter, documentarian, playwright, and photographer. She’s edited and contributed to several books—most notably Crime, a collection of free-ranging interviews with cops, crooks, and artists alike, about the intersection between art and crime; and The Silencing, about murdered journalists in Russia. She also directed the Independent Spirit Award-nominated, feature-length documentary, The Mark of Cain, about the history and symbolism of Russian prison tattoos, for which she gained deep access to Russian prisons and their inmates. It was her work on The Mark of Cain that got the attention of television scribe extraordinaire David Milch, when she was working as an extra on the set of his seminal HBO show Deadwood, a revisionist western that deals with many of the themes of Lambert’s own work. Their meeting led her to become a writer for the show, which in turn led to her writing and producing his follow-up drama, John From Cincinnati, a dense, surreal ensemble drama which sets the surf community of California’s Imperial Beach as the site for God’s divine intervention in order to stop on oncoming holocaust of Muslims at the hands of the U.S. (I know—it sounds awesome, right? If you haven’t seen it—and chances are you haven’t—seek it out immediately). On top of these projects she has also managed to work on gallery shows of her photography; turn Crime into a stage play; and start on a couple other intriguing documentaries involving, respectively, serial killers and teen suicide. She took time out of her busy schedule to have an online chat with The Creosote Journal.

How do you account for the subject of crime taking up so much of your work—from Deadwood to The Mark of Cain to Crime to The Silencing?

I am interested in a very wide range of subjects, but crime is a lens through which to look at the world. I find it magnifies human emotions and actions and shows us ourselves how we might want to be, how we are, and how others might perceive us.

When I made The Mark of Cain, I was actually interested in the dying art of the prison tattoos, but once you make a film like that—the domino-into-crime-effect comes into play, meaning one thing leads to another. I made The Silencing because Paul Klebnikov and his brother Peter helped me with The Mark of Cain, and Paul was one of the journalists murdered in Russia.

So I wanted to shine a light on what was going on there with so many journalists being murdered.

You say ‘the dying art of prison tattoos’. I was unaware that that was the case. What accounts for it becoming a dying art?

The prison tattoos (or “camp” tattoos) provided a hierarchy for the prisoners.

As Russia changed and opened up, status in prison could be bought with Adidas clothes, or money. Also, younger prisoners imagined that they might one day get out and not want to be marked as a criminal for life. The older prisoners made a permanent life for themselves in prison and needed to establish rank, communicate without the guards being able to know what they were saying.

Meanwhile, the crimes that people were sitting for changed. Younger prisoners were coming in on drug charges. There was a clear division, a difference in thinking, between the older prisoners and the younger prisoners. Many prisoners decided to remove tattoos by burning them off. But the tattoos told a story of the whole prison system, and of Russia itself in a state of change.

For most people, a prison is the last place they would want to spend any time. Not just out of a very natural fear, but because of issues of moral judgment.

I certainly hope I never spend any time in any prison (except as a filmmaker).

I just mean as a visitor, not even an inmate. But in your case—as well as someone like Mark Salzman, who you interview in the book, who gives writing lessons to inmates, or John Cheever, who did the same—there seems to be a great sympathy for the prisoners. As a writer, do you think it has to do with mere curiosity, or is there a drive to connect to them as individuals as well as subjects?

Well, I am not overlooking the terrible crimes that some of these people have committed. But I do think we have a dire need for prison reform all around the world. I don’t think it is mere curiosity, I think it has more to do with understanding ourselves by looking at others who are dealing with more extreme experiences, which at first seem like very foreign experiences to ours.

And yes, I think there is a desire for human connection, an ability to understand that most of us, given a certain set of circumstances, are capable of many things we think we are not capable of.

There are of course, sociopaths, and psychopaths, and people whose brains are wired differently—but there is also value, I think, in looking into ourselves and not being so quick to point a finger and label as “other” and therefore absolve ourselves of culpability. Many problems of the human condition are systemic and far-reaching and complex. I am never interested in the easy answer, because I find that it is often wrong.

When it comes to those people that are just wired differently—psychopaths, sociopaths—as a writer and journalist would you have been any more wary of interviewing them? If you’d had the chance, say, to talk to Charles Manson or Richard Ramirez, would you have taken it?

Yes, if I had the chance I would. I would talk with anyone.

I just finished a feature length documentary which I co-directed with David McMahon about a serial killer in Louisiana. He refused our request to speak to him, but the film is narrated using his interrogation tapes. It is very interesting for me to listen to how his voice and presentation of self changes over the course of the 17 hour interrogation. Of course, our film is not 17 hours. But it is a rare thing for an audience to hear.

The killer is named Ronald Dominique and he is one of the most prolific serial killers in American history, but no one has heard of him. The film explores the community, as well as the questions surrounding why no one knows about him.

You were a writer on Deadwood—which, in my humble opinion, alongside The Wire, comprise two of the major narrative artistic achievements of the last decade. Now that I’ve got my gushing out of the way, I was curious as to how you became a writer on the show.

I loved working on that show. I learned so much from David Milch (creator and head writer). I came to that in an odd way. I knew Janie Bryant, the costume designer on the show. She had me come up to be an extra—she put me in a great whore costume. She also told David that I had made this documentary about the Russian prisons, and he started talking to me about the time he met Solzhenitsyn. He eventually asked if I had ever written a script. I had written a feature-length screenplay called Return From Mars that is based on a true crime story in Brooklyn. I actually wrote it because I want to direct it.

But I gave it to him and I guess he liked it well enough to hire me as a writer on the show.

You were also a writer/producer on John From Cincinnati, which is a show I love and will defend to the bitter end, but towards which there is a lot of general dislike—either because of how weird and surreal it is, or because there’s an idea that Milch canceled Deadwood to get it made. What was your take-away from your time on that show, and what do you thinks its legacy is/should be?

People either seem to love or hate that show. There is little in between. I’m glad you are defending it! I also defend the show. I think it tackles some very difficult issues. Unfortunately, with only one season, it’s hard to know where it would have gone, or if it would have gained a larger audience. But maybe I love it because I come out of a fine art background—I think for the main stream, it seemed too weird.

David did not cancel Deadwood to do it.

Honestly, it probably wouldn’t have found much larger of an audience, only because of how difficult it is. But it’s difficult in such a rewarding way. It’s like how Ulysses or Finnegan’s Wake are well known but not widely read.

Yes. Like I said before, for me—in life, and in art—I am never in search of “easy,” but rather in “rewarding.” The most challenging things in my life have always been the most rewarding. I think it is good when something or someone makes you actually pay attention.

So when it came to Crime, you said that you were led to it rather naturally after having done The Mark of Cain. But when did you figure out exactly what it was you wanted to put together and publish?

Well, Damon Murray and I had started talking—we met mostly because he and Stephen Sorrell (Fuel Publishing) had published The Encyclopedia of Russian Criminal Tattoos (beautiful books). And back then, really my film and their books were the only things out there on that subject, so the same people had been contacting both of us about various things—so naturally we started talking. We wanted to make a book together. I had a number of interviews about crime that had never been seen anywhere. We wanted to be more specific than that.

I was working on Deadwood at the time, so he and I started talking about real life crime vs. how crime is represented in the arts. That seemed like a great jumping off point, as both of us have backgrounds in the arts. We just kept talking: who should be in the book, what kind of collection of interviews did we want? And as you pointed out in your review, I settled on something rather personal.

Although, that having been said, there were people like Takeshi Kitano that we just wanted to include.

It was a fairly organic (a word I don’t love, but I am not coming up with a better one in this moment) process. Damon and Stephen and I all wanted the book itself, as an object, to be a work of art, hence the photographs and design. I love books, the physicality of them.

This isn’t the type of book that you’d want to experience on an e-reader.

Exactly! I think the e-reader is a great thing. I think it serves a purpose. But it is not right for every book. And it would not be right for this one. I always tell people if they don’t want to read it, they can knock someone over the head with it, and then use it as ballast to weigh the body down.

As you said, one of the themes of the book is the intersection between art and crime, and you get many of your subjects talking about the art that meant something to them, or which they felt were the best representations of what they experienced first hand. What are some examples that you’d give, personally, of films or books about crime that had an impact or influence on you?

I mention some in the introduction: the Jean Harris case, and the Leopold and Loeb case were early fascinations for me. I read Leopold’s book that he wrote in prison. Also In Cold Blood, both the book and the movie. But gosh—the list is sooo long. Dream Deceivers and Paradise Lost were documentaries that I used to always show my documentary students. Man on Wire was a great marriage between crime and art and such a well made film. Or rather its subject was a great marriage…

If you could have reached back into history to interview any figures for this book, or even someone today that you didn’t have access to, who would it be?

I would have liked to include Philipe Petit actually, by the time that idea popped up we already had a 500 page book that needed to be edited down. Historically—one has to define crime—it would have been nice to include Joan of Arc.

You’re a writer, filmmaker and photographer. Which form did you take to first, and do you consider yourself one more than the others?

I started in photography, video art, conceptual/performance art, and filmmaking.

I think I am better at telling stories visually than I am with words. Or at least it feels like more of a struggle for me to write than to direct.

With visual storytelling, I just see in my head what I want. It kind of appears. With writing I have to rip it out of myself and then feel very insecure about it.

Crime reminded me of James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, about US Southern sharecroppers during the great depression. Agee said he wanted to intrude as little as possible with words, and mostly let the photographs (by Evans) tell these peoples stories, as well as allowing them to present themselves in their own words.

Well, I am thrilled and humbled that it reminds you these great, talented men. I always want people to tell their own stories to the extent that they are able… I just want to facilitate their ability to do that and then get out of the way. Even when I am directing fiction. I think you have to trust what will happen—and let the work tell you what to do rather than the other way around.

What’s next for you?

I am in production on a feature documentary called Mentor about a case where five kids at Mentor High (ironically titled) committed suicide as a result (their families argue) of being bullied. I head back to Ohio to continue shooting in about 10 days.

Then in August my play CRIME, USA will be staged in Cairns, Australia, at a festival there, so I will go with four actors to Australia to stage it. In the fall I will develop for RealArtWays a new version of CRIME, USA but it will be CRIME, USA, HARTFORD. We just received an NEA grant, and I’m excited to work with RealArtWays on this.